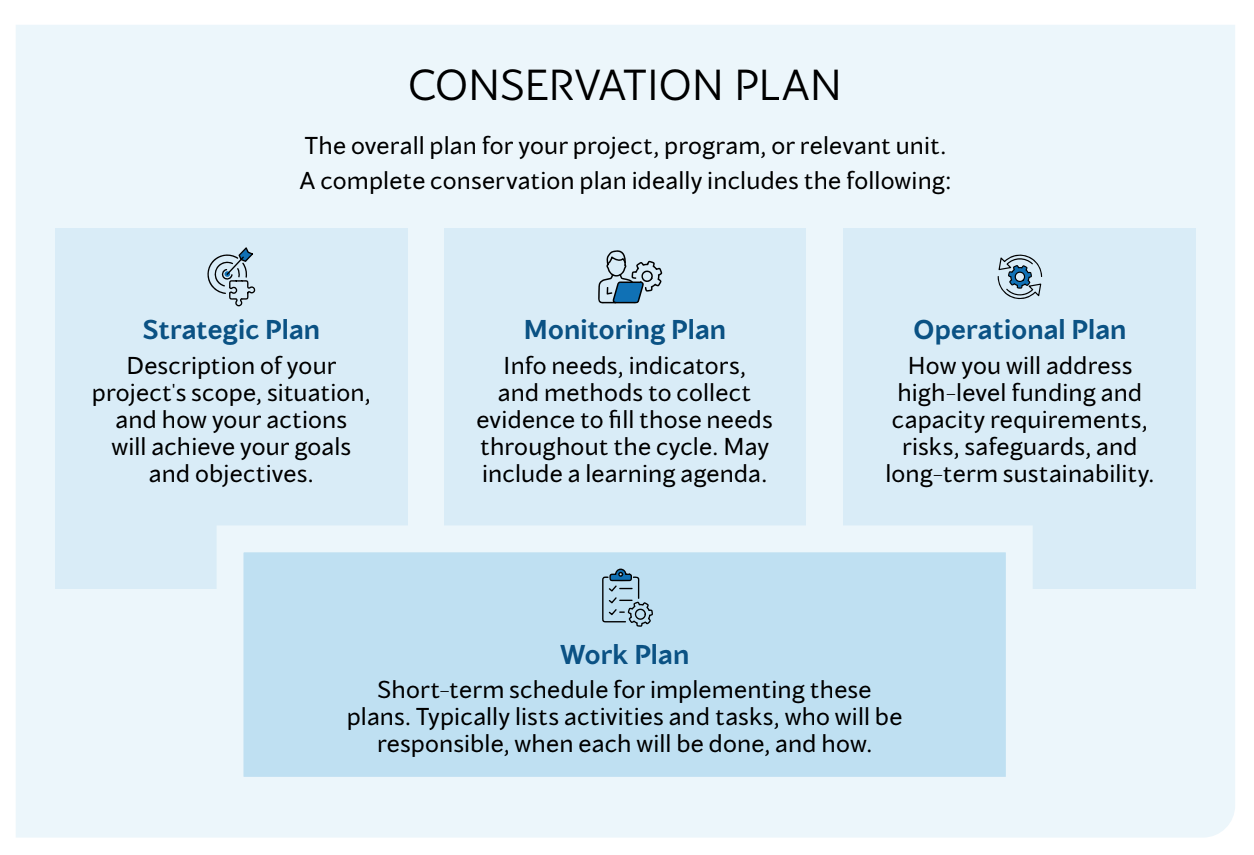

This step in the Conservation Standards cycle focuses on developing key components of your overall conservation plan . Specifically, it involves using and building on your work in the Assess Step to define and develop your project’s scope, actions, theories of change, and associated goals and objectives (i.e., your strategic plan ). It also involves clarifying specific information needs and indicators and how you will monitor these (monitoring plan) and laying out how you will operationalize your work, considering various institutional and contextual factors (operational plan). As shown in Figure 1, all this information contributes to your overall conservation plan. Step 3 Implement includes more information on the work plan element.

Figure 1:Relationships among different plans. Source: Adapted from Stewart 2016. Operationalising the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation.

As with many of the Conservation Standards steps and sub-steps, much of what you do in this step will be iterative. For example, although you develop an operational plan in Step 2C, you may need to think about sustainability, risks, and transition plans as you are choosing your actions in Step 2A. These elements may help your team and senior managers determine whether to continue with a specific action or even your overall project.

2A. Develop Strategic Plan¶

Goals

Developing a clear idea of what you would like to accomplish is an essential early step in putting together your strategic plan. Goals are linked to your project’s focal values (conservation and/or human wellbeing) and represent the desired status of those focal values over the long term. They are formal statements of the ultimate impacts you hope to achieve. A good goal meets “SMART” criteria: specific, measurable, achievable, results-oriented, and time-limited (see Annex 2 and Box 6). As with every step of your plan, your goals will be heavily influenced by the values of the team involved in their development. Be sure you are including a variety of perspectives from many interested parties.

BOX 6: SETTING GOOD GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

Good goals and objectives should meet the following SMART criteria:

Specific – Clearly defined so that all people involved in the project have the same understanding of what the terms in the goal or objective mean

Measurable – Definable in relation to some standard scale (numbers, percentage, fractions, or all/nothing states)

Achievable – Practical and appropriate within the context of the project and in light of the political, social, and financial context (especially relevant to objectives; goals may be more aspirational)

Results-Oriented – Represents necessary changes in focal value condition, threat reduction, and/or other key expected results

Time-Limited – Achievable within a specific period of time, generally 1-10 years for an objective and 10-20 years for a goal.

Ideally, your project goals should fit within and contribute to broader program and/or organizational goals. Indeed, in some cases, what your project is expected to achieve may be specified by your organization and/or statutory requirements. These external obligations may ultimately influence your team’s prioritization of actions. Where possible and relevant, your team also should consider the opportunity to align your goals – (and objectives discussed later) with broader national, regional, and/or international efforts (e.g., the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Sustainable Development Goals, Convention on Biodiversity, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) and specify how your project intends to contribute to these wider efforts. You should not force this connection, but rather look for where there is overlap and potential for alignment.

If you did a viability assessment in Step 1B, you have already defined the elements of a good goal because you know the key attributes needed for a healthy focal value, you know by when you hope to achieve the desired status, and you know what you need to measure to assess its health. Developing a goal is just a matter of converting this viability information into a goal statement. As an example, a SMART goal for the forest corridor biodiversity focal value in Figure 4, Asesss Chapter might be: By 2035, the forest corridor linking the White River Watershed to Los Grillos is at least 5 km wide and remains unfragmented.

If a project has human wellbeing focal values, then goals should be set for these focal values. To do so, the team can define key attributes needed for a healthy human wellbeing focal value.

In a conservation project, these attributes are typically tied to the ecosystem services provided by a biodiversity focal value and/or expected results from conservation actions that directly benefit human wellbeing. It is good to keep in mind that there are many dimensions to human wellbeing, not all of which could be attributable to conservation work. For example, a conservation team would probably not have human wellbeing goals related to decreasing cholesterol levels, even though heart disease prevention is important for human health. It may, however, have human wellbeing goals related to access to food sources because the conserved biodiversity focal values are improving crop pollination services. In some cases, however, projects may have an equal focus on biodiversity and human wellbeing. Your team will need to be clear about the scope of your human wellbeing work and what human wellbeing goals make sense for your project. Likewise, it is important to understand when conservation and human wellbeing goals may be in conflict with one another and to be clear about what your project can and cannot achieve. Remember that all human wellbeing goals should be developed in partnership with the relevant groups identified in your interested parties assessment.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 4: SETTING GOALS

When using your viability assessment to set goals, you should review how projected changes in climate may affect each biodiversity focal value and ensure that your goals capture a desired future state that is climate informed and attainable. In setting your goals, consider whether you are trying to maintain or return to a historic ecological state, accept ecological change without intervention, or direct change towards a forward-looking ecological state. Even if your threat assessment indicates that a biodiversity focal value may be lost, it is best not to remove it until you have explored potential actions (later in the process). Keep in mind that you may need to revisit your goals as you go through the planning process.

For projects whose primary aim is to avoid, reduce, or sequester greenhouse gases (GHGs), your goals should describe which ecosystems and/or working lands and waters need to be conserved, managed, and/or restored to achieve this change in GHG emissions (e.g., By 2035, at least 100,000 hectares of peatland páramo in the Andes are restored to sequester carbon in soils). ::

Actions

Once you determine what you ultimately want to achieve (your goals), you should think about what you need to do (actions and activities). Good strategic planning involves determining where and how you will intervene, as well as where you will not. It also involves transparently and inclusively identifying whom you need to influence, who holds historical power, and whose voices need to be elevated.

Selecting Key Intervention Points

When developing your actions, you will want to prioritize the factors you need to influence to improve the context outlined in your situation analysis and/or model – these are the key intervention points . To identify key intervention points, you need to evaluate all factors and, using available evidence (including traditional knowledge), identify which ones show good leverage opportunities and are likely to impact the focal value the most. Some considerations to evaluate leverage potential include contribution to threat abatement, ability to influence multiple factors in the model (including motivations for and barriers to behavior change), and urgency of addressing the factor (or its downstream factors).

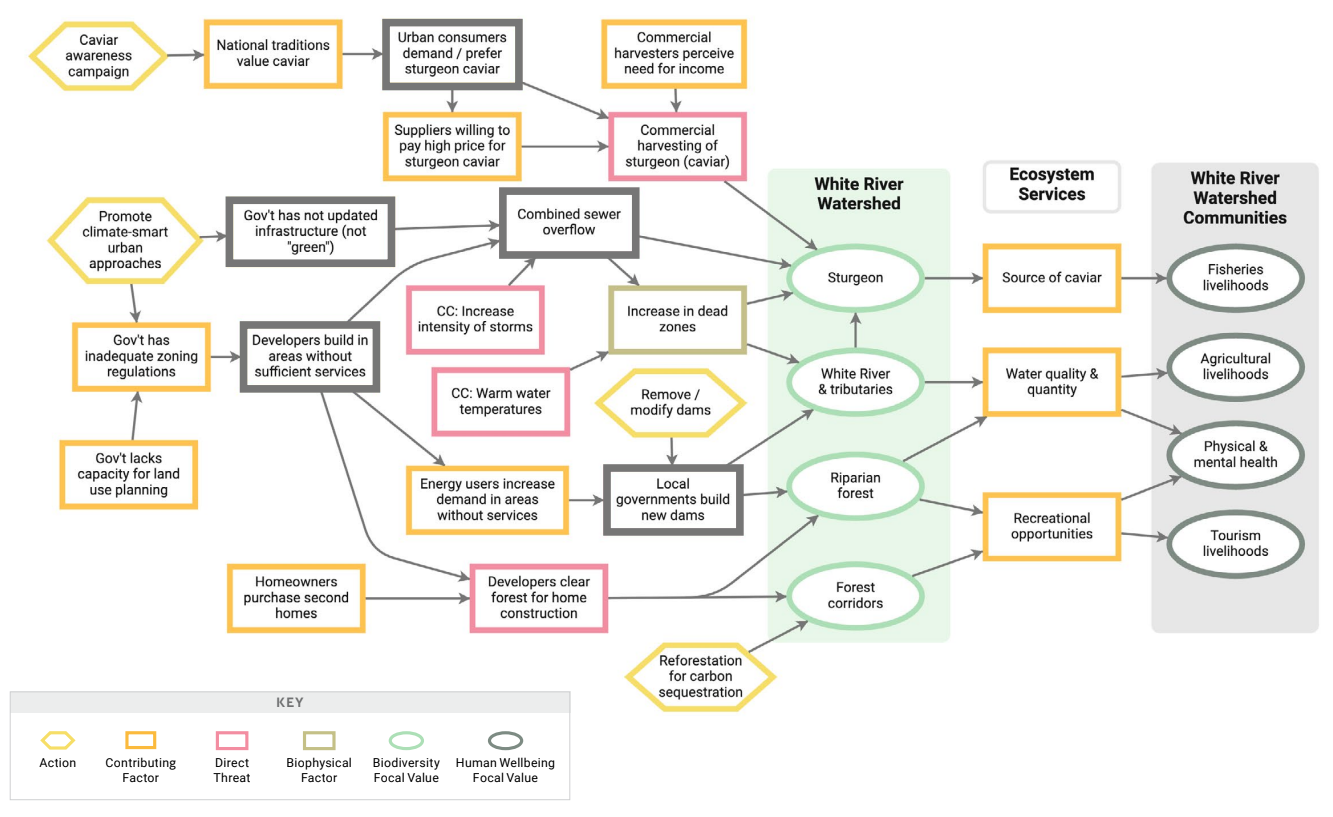

In theory, any factor in a situation model offers an opportunity for intervention. In some cases, the obvious key intervention point is the direct threat itself (e.g., removing or managing invasive species) or the biodiversity focal value (e.g., restoration of an ecosystem). But in many other cases, you will get more leverage if you intervene on an indirect threat or opportunity that is part of a chain of factors affecting a direct threat (e.g., influencing policy or promoting good management practices). Your team’s leverage on a factor may depend on your relationship with the actors involved in that behavior. Figure 2 shows an example of key intervention points and actions (depicted as hexagons) to address them.

Figure 2:Example situation model with key intervention points (bolded boxes) and actions.

Deciding How and Where You Will Intervene

Your key intervention points help you determine where you need to consider conservation actions to influence your overall situation. The Conservation Standards define an action as a set of one or more activities with a common focus that work together to achieve specific goals and objectives by targeting these key intervention points, optimizing opportunities, and limiting constraints.[9] Actions should meet the following criteria: linked, focused, feasible, and appropriate (see Annex 2). Actions are implemented in the context of a strategy, which includes one or more actions and their associated expected results and goals and objectives.

BOX 7: BEHAVIOR CHANGE LEVERS

For human behavior change, we can use a set of behavioral levers (behavior-oriented strategies) based on established principles of behavioral and social science. These levers help describe the pathways linking actions to desired change in key actors’ psycho-social states and ultimately in their behavior. These levers are most effective when used in combination to address the different motivations or barriers actors have at institutional, social, and individual levels. These levers include:

- Providing information and support (show/teach me)

- Changing incentives (e.g., material costs and benefits, time, and effort) (tempt/ help me)

- Enacting rules and enforcement (make me)

- Using social influences and norms (norm me)

- Leveraging emotional appeals, key values, and interests (sway me)

- Designing the choice or decision context (nudge me)

Knowing which type of lever and specific action to implement depends on understanding the interests, context, cognitive biases, barriers to, and motivations for each key actor’s or interested party’s behavior.

There are many types of actions that can be used for different purposes, such as directly managing ecosystems or species, influencing human behaviors (Box 7), or creating enabling conditions that contribute to strategy effectiveness (see IUCN-CMP Conservation Actions Classification for a completelist of potential actions). Working off your situation analysis, you should generate a list of possible actions to influence your identified key intervention points.

It is good practice to test your actions to see how well they work before implementing them. If you determine there is strong evidence that an action will be effective in a project’s context, you can then implement it at the appropriate scale. If the evidence is more mixed or not available, you may wish to conduct additional testing or pilot the action and use adaptive management to determine its effectiveness for your context. If you do move ahead with actions that lack sufficient evidence of effectiveness for your context, it is wise to consider the risks to your project of doing so and also make sure you closely monitor the action.

Finally, it is important that your project has appropriate environmental and social safeguards in place. This involves assessing approaches to avoid or mitigate potential adverse social and environmental effects of your actions, especially on interested parties with low influence and high interest. Throughout the project, your team will need to regularly consider the vulnerability, dignity, human rights, traditional knowledge, land and resource ownership, and cultural heritage and practices of affected groups. It is important to identify unintended consequences, feedback loops, and tradeoffs that can occur and that can affect people, biodiversity, and your project itself. While it is useful and prudent to review social and environmental safeguards throughout the project cycle, it is especially important in the strategy design phase, as strategies and actions may need adaptations or considerations to avoid, minimize, or mitigate potential negative effects.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 5A: IDENTIFYING STRATEGIES TO INCREASE RESILIENCE TO CLIMATE CHANGE

Consider a diverse array of strategies that address both the complexity and uncertainty of ecological responses to climate change. This table shows how considering your work from earlier CS steps (especially viability assessment and threat rating) can help you identify strategies to increase the resilience of your focal values to climate change.

| Intervention | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Maintain or enhance the viability of a focal value and increase its capacity to adapt to climate change | Protect land to allow inland migration of tidal marsh as sea level rises, accepting change in coastline |

| Protect climate refugia by protecting and/or restoring occurrences of the focal value that may be less exposed to changes in climate | Protect sections of a stream in which cold groundwater inputs continue to provide habitat for cold water fish species as other areas become warmer |

| Reduce the biophysical effect of a climate- related threat (e.g., increase in water temperature) by acting on a non-climate threat contributing to the same biophysical effect | Provide habitat for coldwater fish by protecting riparian vegetation that shades the stream as air temperature increases |

| Prevent human mal adaptation or actions that increase climate vulnerability Example strategy to increase climate resilience | Work with Indigenous Peoples to reinstate natural fire regimes in areas where human actions have altered the frequency and intensity of fire |

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 5B: IDENTIFYING STRATEGIES FOR CLIMATE MITIGATION

Natural climate mitigation pathways can help countries meet their nationally determined contributions to the Paris Agreement. These climate mitigation pathways focus on conserving, managing, or restoring forests, wetlands (including mangroves and peatlands), and agricultural lands. The table below provides examples of strategies and GHG emissions impacts for some of these mitigation pathways.

| Pathway | Impact | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Restore mangroves | Sequesters GHGs | Breach water control structures to restore hydrology and increase mangrove cover |

| Avoid forest conversion | Avoids GHG emissions | Strengthen law enforcement to prevent conversion of forest to illegal gold mining |

| Manage forest | Reduces emissions | Strengthen guidelines for natural forest management in government forest concessions |

Assumptions & Theories of Change

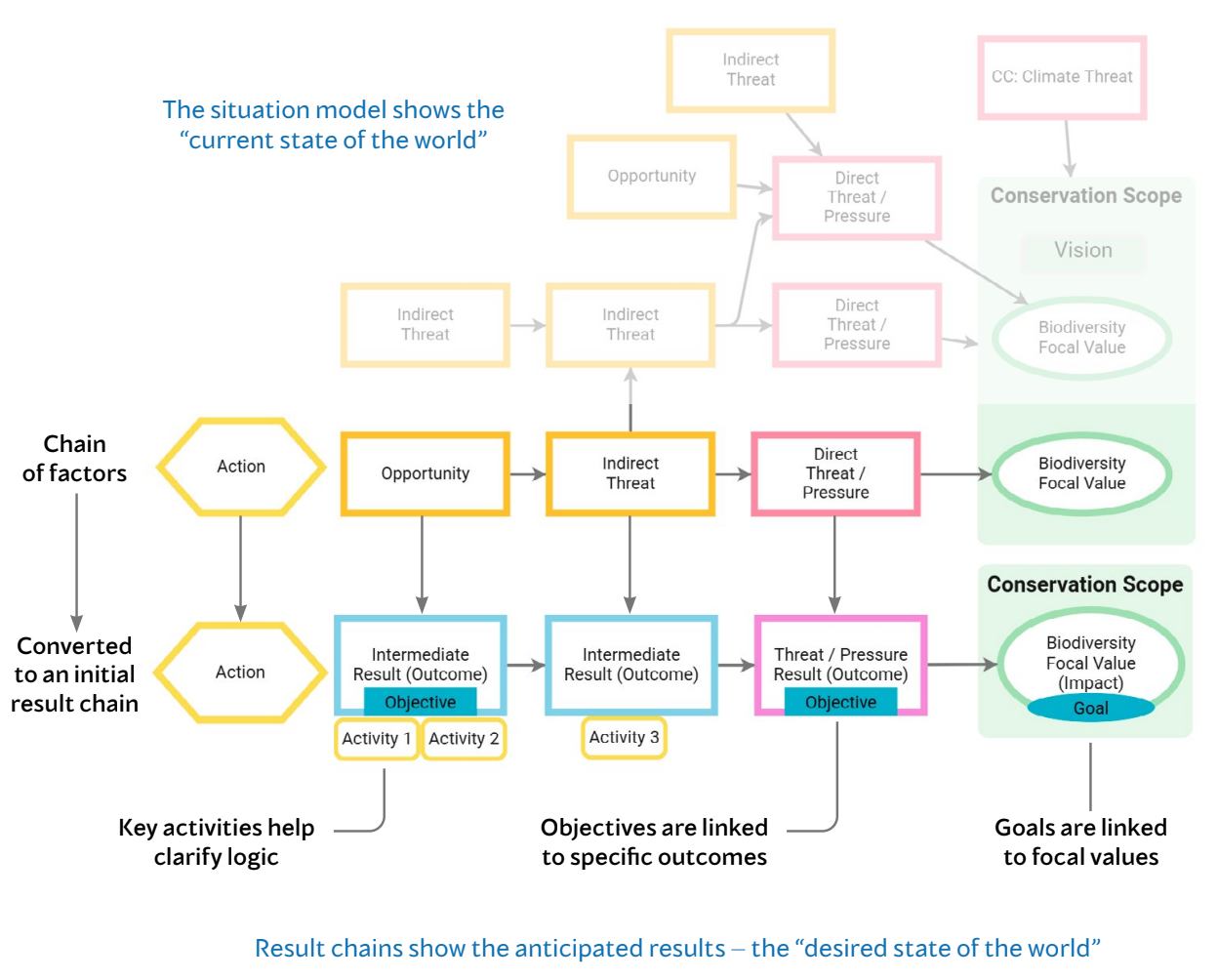

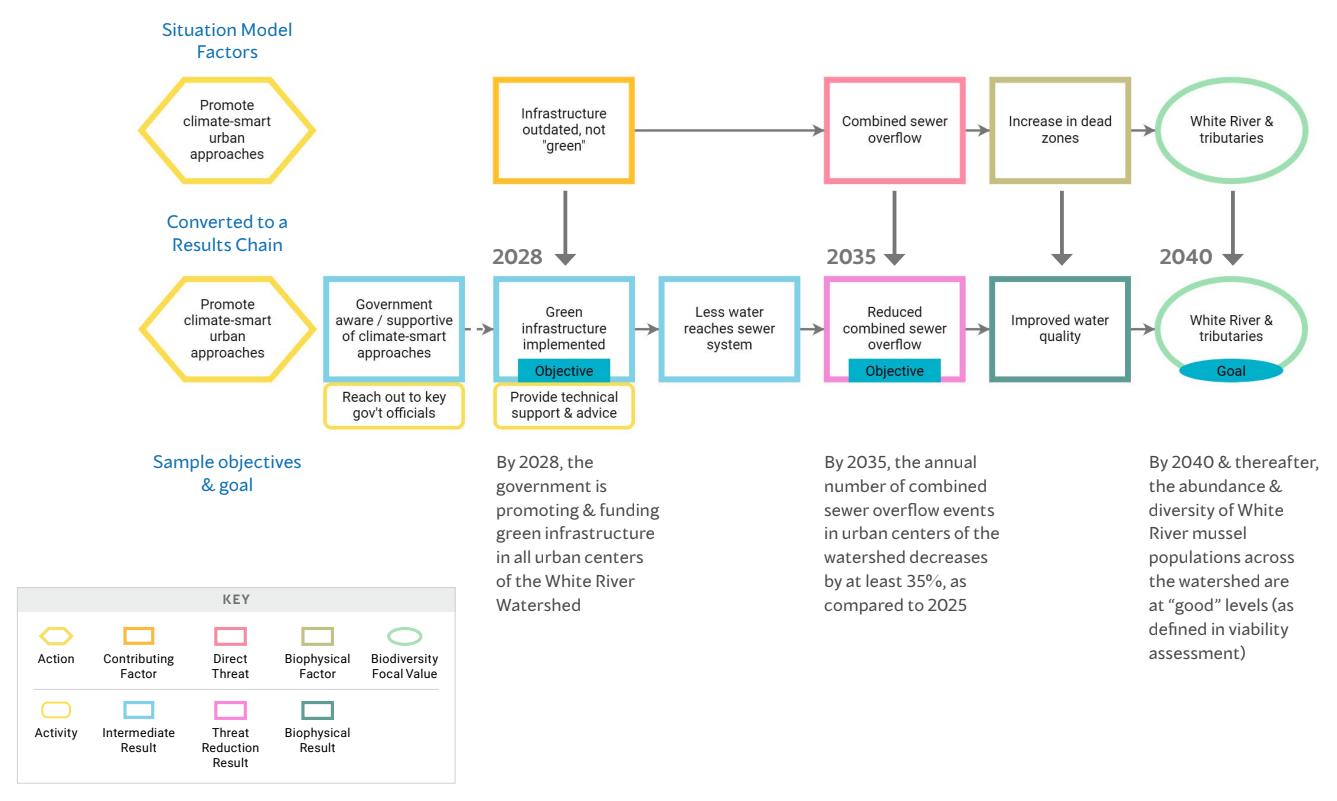

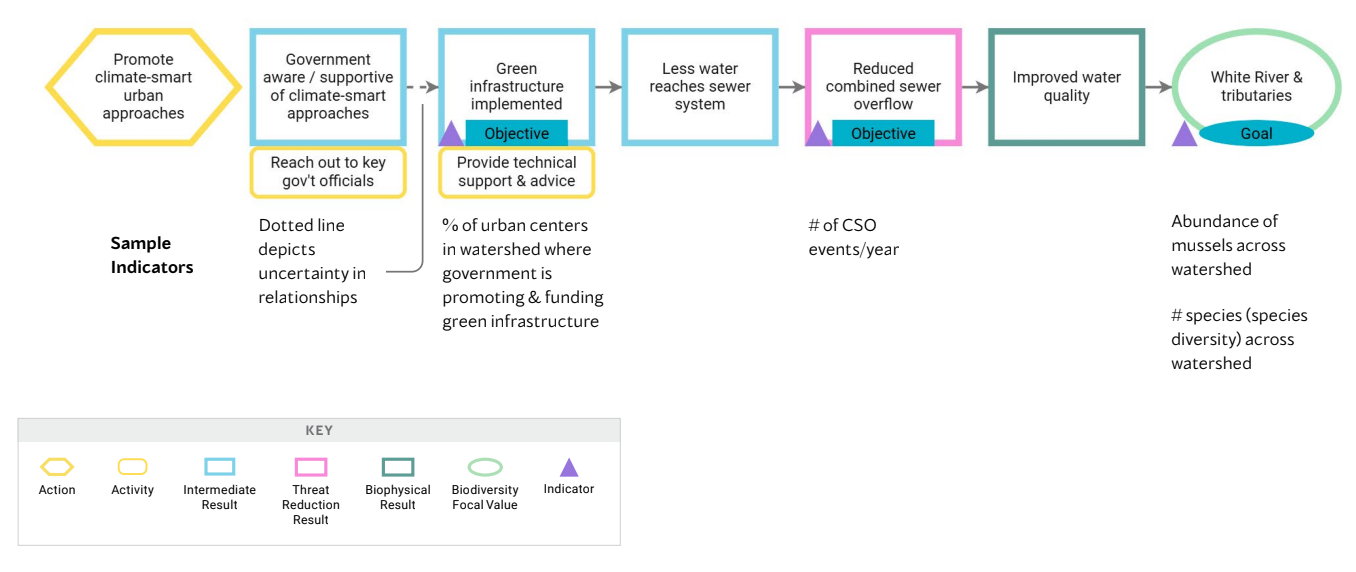

Once your team has selected your actions, you should clarify the causal assumptions about how you think each action will help you achieve intermediate results and longer-term biodiversity and human wellbeing goals. These assumptions, as well as assumptions about other factors that need to be in place for your action to succeed, represent your theory of change . Your theory of change can be expressed in text, diagrammatic (i.e., results chain ), or other forms.[10] If you portray your situation analysis in a situation model, you can use that as the basis for developing your results chains (Figure 3 shows a generic example, while Figure 4 shows an example based on Figure 2). Doing so helps you explicitly show how your action is intended to affect the current state (portrayed in your situation model) to achieve the desired state (portrayed in your results chain). While the results and assumptions in your theories of change should be based on existing evidence, some assumptions may lack evidence. As such, your team may have uncertainty about whether your expected results can be achieved and if there are potential risks of undesirable outcomes. It is important to identify and prioritize these evidence gaps for attention (e.g., the dotted line in (Figure 4) between governemnt aware and green infrastructure boxes indicates an uncertainty in the team’s assumptions).

Often, your results chains (and, more broadly, your theories of change) will include key activities needed to implement your action successfully. Adding these activities can help clarify how you expect to achieve one or more specific results. It is also useful to make sure your results contain information about key psychological and social states (psycho-social states), including actors’ beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and context for their behavior. This will help clarify why you think specific activities will lead to behavioral outcomes. This is a good point to consider your team’s ability to make accurate assumptions about the actors involved, their behavior, and the power dynamics or barriers they may face in changing the situation.

Figure 3:Generic situation model factors with associated results chain.

Figure 4:Example results chain for promoting climate-smart urban approaches in a watershed site.

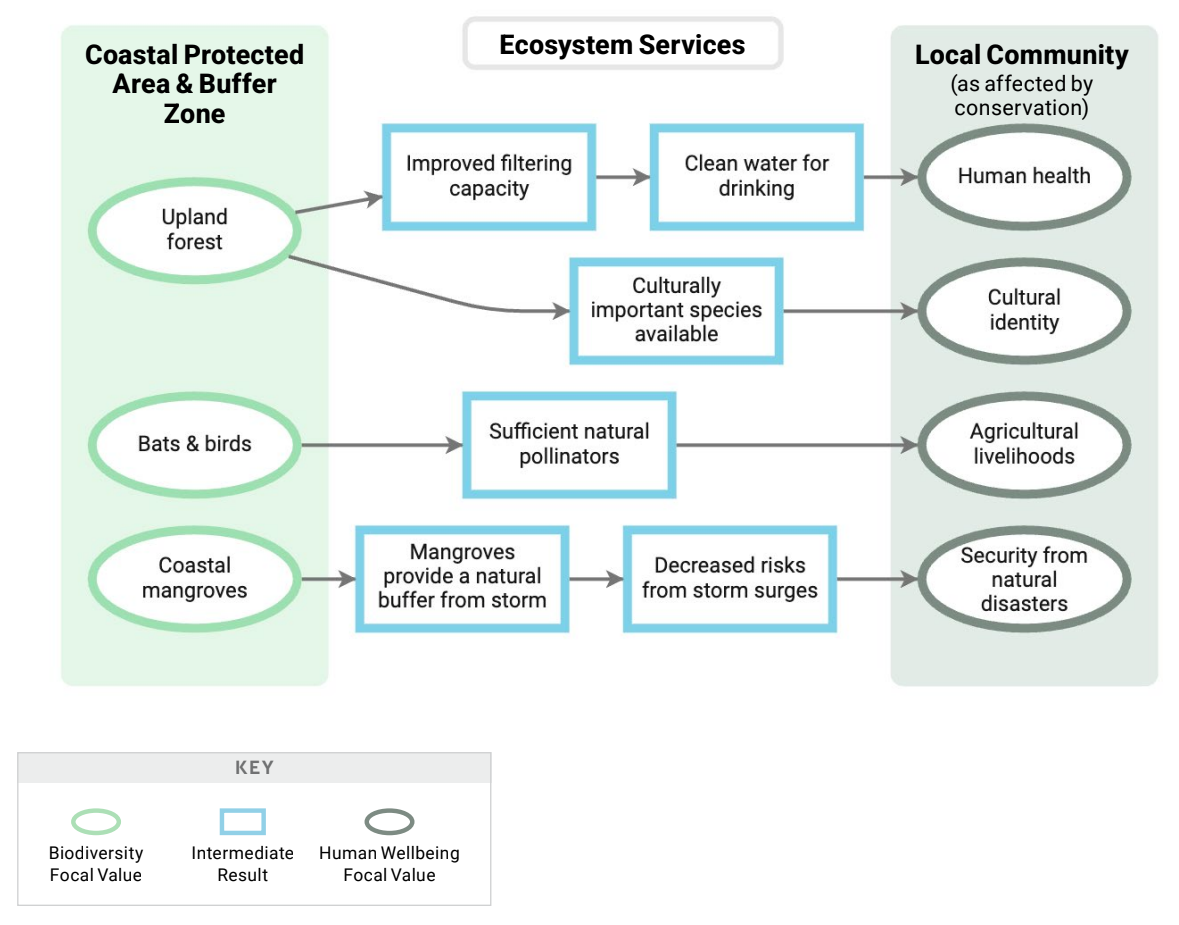

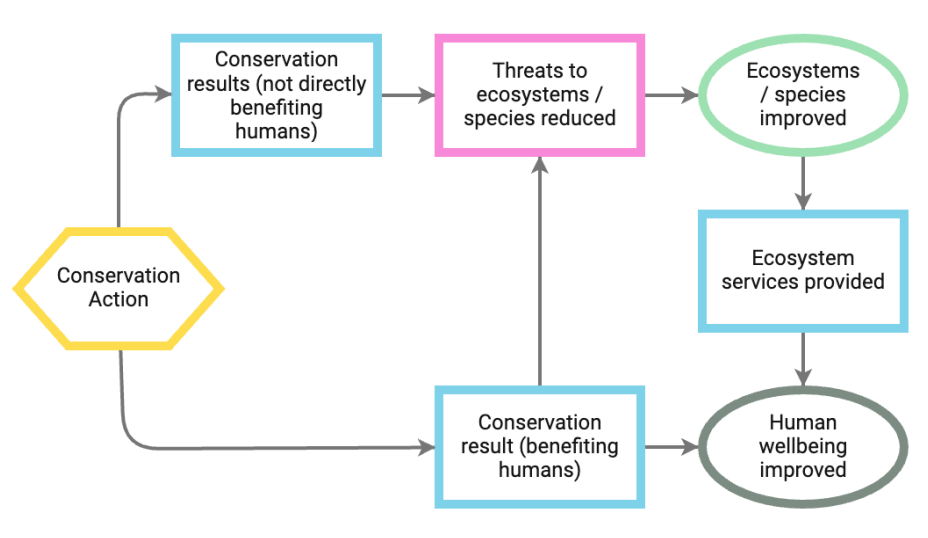

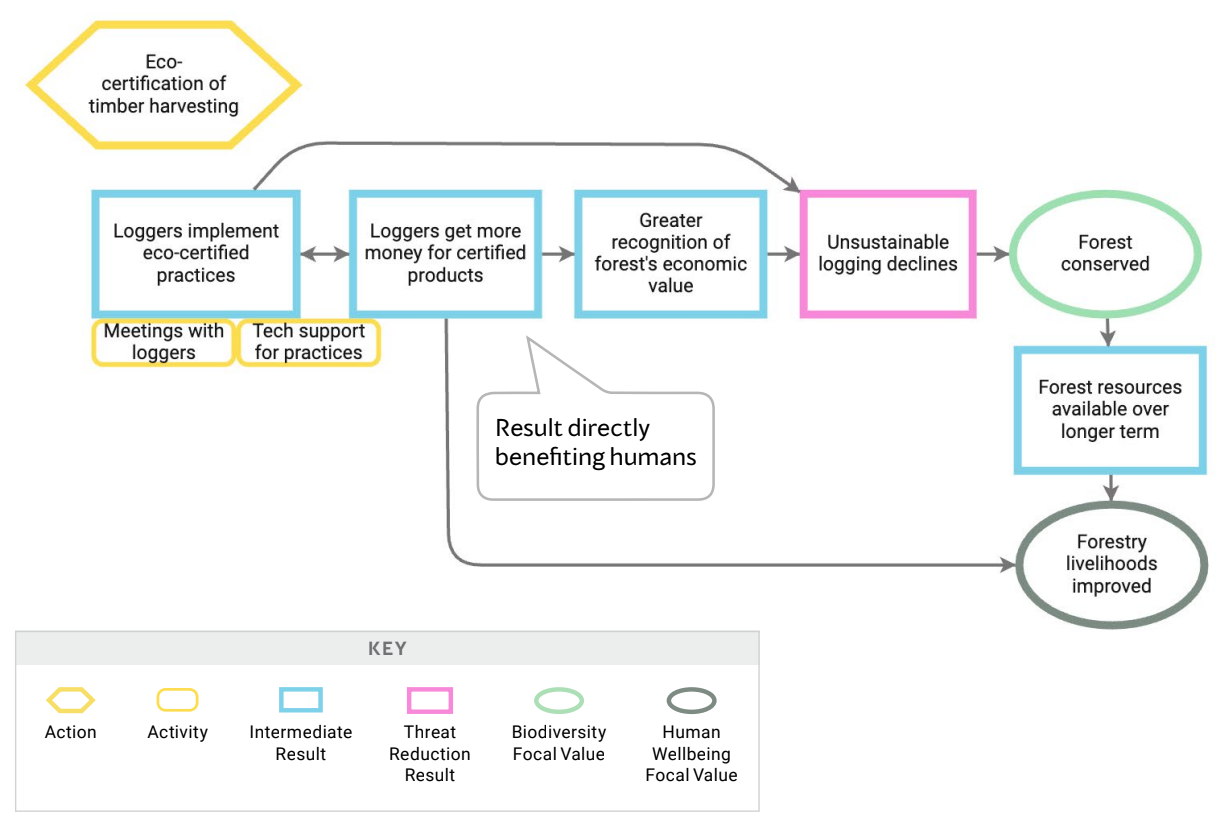

If your team identified human wellbeing focal values in your situation model, you should also use your theory of change to show how you believe your project’s actions will improve human wellbeing (Figure 5 provides an example that shows how ecosystem services might contribute to human wellbeing). Keep in mind that conservation teams also often work on important social issues that have benefits and address interests beyond biodiversity (e.g., building capacity for good governance or promoting sustainable livelihoods). In such cases, the conservation action provides social benefits in service of conservation. It is useful to clarify when your conservation actions are contributing to human wellbeing focal values via ecosystem services and when they are contributing more directly via conservation actions. Figure 6 shows these relationships generically, while Figure 7 illustrates a specific example where an eco certification action could contribute to human wellbeing both directly via increased logger incomes (which is also a necessary result for conservation) and via ecosystem services.

Figure 5:Example results chain extract with ecosystem services and human wellbeing focal values.

Figure 6:High level relationships of how conservation actions can contribute to human wellbeing.

Figure 7:Example of conservation action directly benefiting humans.

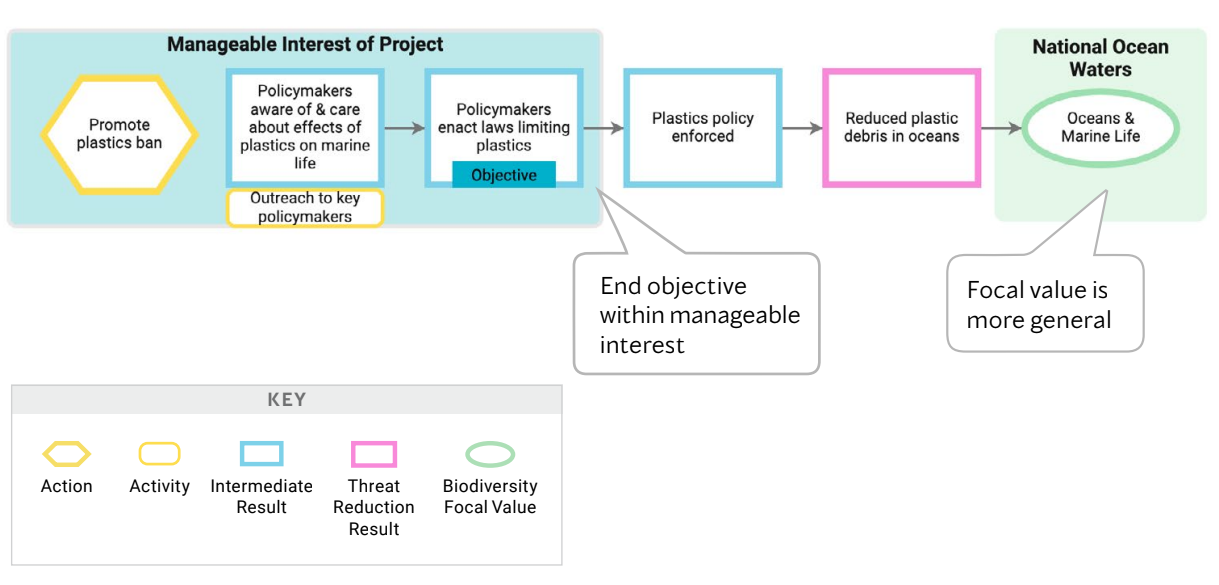

Results chains can be used to show the outcomes of the project’s specific work, as well as longer-term outcomes that may be beyond the manageable interests and/or timeframe of the project. Some projects may hope to achieve improvements in their focal values, while others may only intend to get as far as a threat reduction result (e.g., reduced plastic debris in oceans, Figure 8) or even an intermediate result (e.g., policymakers enact laws limiting plastics). In these latter cases, the ultimate threat reduction and/or conservation result may be more implicit than explicit.

Figure 8:Project example with a manageable interest not directly tied to biodiversity.

Objectives

Objectives are formal statements of the outcomes (or intermediate results in your results chains) that you believe are necessary to attain your goals. Objectives specify the degree of change that your team assumes is necessary to achieve in the short and medium term. Your objectives should be clear about the actors and the desired behaviors. Good objectives (and goals) meet “SMART” criteria: specific, measurable, achievable, results - oriented, and time - limited (See Annex 2).

As shown in Figure 4, your objectives are tied to the results that are necessary for your theory of change to hold. It is generally good practice to have an objective for the direct threat (unless this is outside your manageable interest, as illustrated in Figure 8). This direct threat objective (and its target value) should be informed by the goal you set for your biodiversity focal value. It will be important to work through each objective to define what is appropriate and to ensure that the criteria for good objectives are met. You may need to use an iterative approach, revisiting and refining your objectives (and/or your actions and associated theories of change) as more information becomes available. Box 8 includes some additional considerations for setting objectives.

The goals and objectives specified in your theories of change represent what you need to accomplish. Together, with your theory of change, they clarify your assumptions about how your actions will help you reach those accomplishments and how you will gauge the progress of your project.

OTHER CONSIDERTATIONS IN SETTING OBJECTIVES

Some important considerations in objective setting (beyond SMART criteria) include:

- Use existing information to develop your objectives. Where available, it is helpful to understand current or baseline conditions to determine how much change is needed.

- Where appropriate and available, use theoretical models, expert input, and other available evidence to set the numeric value in your objectives (and goals).

- Clarify how much change you need to achieve to see conservation results. Ideally, you should challenge yourself to work backwards from your goal and/or intermediate results to determine how much of each preceding objective you need to keep the chain progressing.

- Given that multiple actions may contribute to a single result, when setting an objective for that result, consider the cumulative effect of these different actions.

Strategic Plan Pulling It All Together

You should capture and document your scope, situation analysis, and actions (including theories of change, goals, and objectives) formally in your strategic plan (refer back to Figure 1). Establishing a structured, technology based system to link your actions to your results, goals, and objectives will enhance tracking and accountability. Depending on your needs and the level of detail required, this system could range from a simple table to something more comprehensive, such as a database, with folder hierarchies to organize and store documents. A clear system will help you keep all relevant data and documentation organized, accessible, and easily updated.

2A OUTPUTS

- Goals for each biodiversity focal value and, if appropriate, human wellbeing focal value

- Identification of key intervention points and draft actions

- Prioritization of draft actions

- Theories of change that clarify assumptions about how actions and associated activities lead to expected results

- Objectives for key intermediate

2B. Develop MEL Plan¶

This sub-step includes outlining monitoring, evaluation, and learning protocols to develop a comprehensive monitoring plan . Your monitoring plan will help you track progress towards stated goals and objectives, evaluate progress along and key assumptions associated with your theory of change, and address information needs related to uncertainties identified earlier (e.g., in your situation analysis, action selection, or theories of change). The monitoring plan will also be helpful in identifying the resources needed for implementation, developing a timeline for data collection and analysis, and reflecting on potential risks. The level of rigor and the type of monitoring you do will depend upon your confidence in your key assumptions (i.e., the degree of evidence to support your assumptions), the consequences of being wrong, the stage of your project, and available resources.

Audiences and Information Needs

To start developing your monitoring plan, you should specify your audiences and their information needs . Effective monitoring uses the minimum amount of financial and human resources to provide you with the information needed to address key uncertainties and/or determine if your project is on track and achieving stated objectives.

As a first step, you should determine for whom you are doing the monitoring, what they need to know for decision making, when they need the information, and what level of rigor is required to meet their needs. For example, one audience might be your project’s funders who need to know you are spending their money appropriately. Another audience might be interested parties (including Indigenous Peoples and local communities) who want to know whether their concerns and interests are being addressed. A key audience for monitoring is always your own project team. Monitoring is essential to help your team track the implementation of actions and achievement of goals and objectives, test assumptions in your theories of change, reduce uncertainties, learn from information collected, and improve current and future programming. Table 1 lists some common audiences and their general information needs.

By focusing your monitoring efforts squarely on the core assumptions you have made (illustrated in your situation model and results chains) and the key uncertainties you have identified, you are more likely to collect only the information that will be useful for addressing specific information needs (e.g., status of threats, achievement of results, areas of uncertainty).

If your monitoring is designed to help understand why actions are working or not, make sure to monitor not just specific results, objectives, or goals, but also key factors that may contribute to or detract from your ability to achieve your desired results. This could include monitoring barriers and enabling conditions beyond your control, as well as changes to behavior and related psycho-social states for key actors. When prioritizing information needs, it is useful to think about the risks to your project of not having this information, how you will use the information for management decisions, and whether it is feasible to address the information needs within the confines of your project’s resources and timeline.

Table 1:Common monitoring audiences and their information needs.

| AUDIENCE | NEEDS |

|---|---|

| Project team | Is your team implementing the activities as expected? Is your team achieving its objectives in the expected timeframes, and are assumptions valid? What is working, what is not, and why? How can your team improve your strategies? |

| Donors | Is your team implementing the activities as expected? Is the project achieving objectives in the expected time frames? Are the assumptions behind this project valid? |

| Interested parties | Is your team implementing the activities as expected? How will the project affect them? |

| Conservation community | What worked, what did not, and why? What may be generalizable from the project to other contexts? |

| Academics & students | What worked, what did not, and why? |

| Auditors & certifiers | Is the project complying with laws and regulations? Is it following best practices? |

Indicators

With your audiences and information needs identified, the next step is to define the specific indicator data and other information you should collect to address your information needs. Good indicators meet the criteria of being measurable, precise, consistent, and sensitive and should be tied to key factors, results, or assumptions in your situation model or theory of change (see Annex 2). Note that some indicators may be qualitative, while others may be quantitative. Likewise, as discussed below, there are a variety of methods to measure any single indicator. Where relevant, indicators also should be informed by the perspectives and values for biodiversity held by Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 6: MONITORING CLIMATE CHANGE EFFECTS AND STRATEGIES

While adaptive management is always important, it is particularly critical when dealing with the variability and uncertainty around climate impacts. To monitor climate and/or the reaction of particular species and ecosystems to climate change, you may need to use special monitoring approaches (e.g., using specific indicators for soil moisture, storm frequency, and storm intensity). It is important to identify threshold levels for specific indicators (e.g., the threshold between “good” and “fair” in your viability assessment) to use as triggers to consider adding, modifying, or removing strategies or to reconsider a focal value.

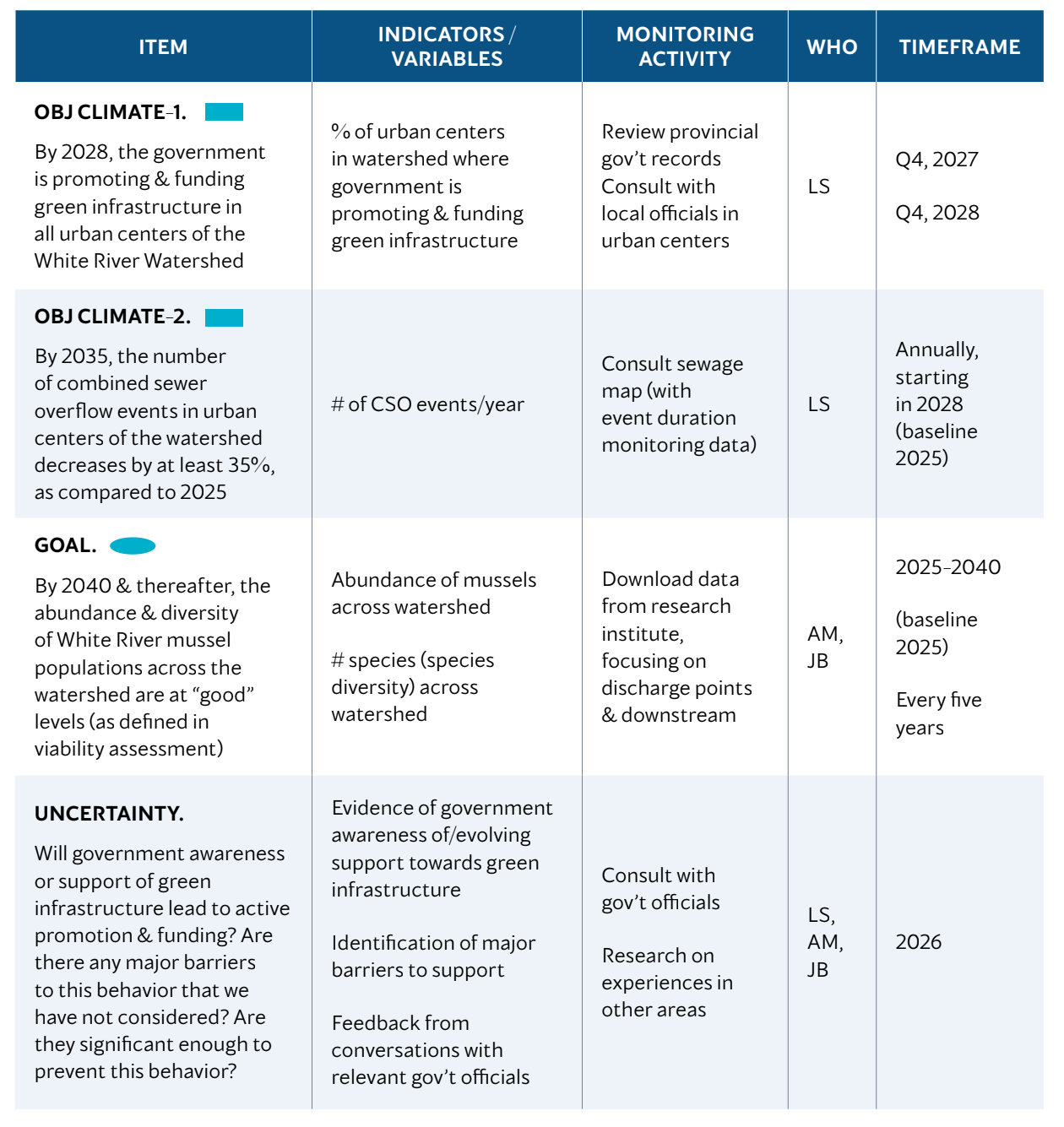

Through your situation model, theories of change, and goals and objectives, you have clarified your focus and prioritized your information needs. These could include: addressing gaps in your situation model, testing assumptions in your situation model and results chains, and demonstrating progress towards achieving stated objectives. These inputs will help you narrow down a nearly infinite set of potential indicators to a more manageable list and provide you with a solid framework for focused data collection, analysis, evaluation, and learning. Figure 9 provides an example of how theories of change and associated SMART objectives can help you focus your indicators. You should aim to collect the minimum data required to meet your critical information needs. As you monitor progress along your theory of change, keep in mind that there may be important factors that are outside your team’s control but that could have an important influence on the success of your action (e.g., political situation or market forces). In these cases, you may want to monitor these factors with a limited set of indicators to help you interpret whether you are achieving your expected results (and why or why not).

Figure 9:Conservation-friendly zoning results chain with potential indicators.

watershed species (species diversity) across watershed government is promoting & funding green infrastructure Indicators uncertainty in relationships

Methods

As you develop your indicators and identify key information needs, you will need to think about how you will measure them (i.e., the methods you will use). Examples of methods could range from conducting wildlife survey transects to downloading satellite imagery on land use patterns to conducting key informant interviews to understand interested party attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and behaviors. Methods should meet the criteria of accurate, reliable, cost effective, feasible, and appropriate (see Annex 2). Where possible, monitoring methods should be participatory, non extractive, and address privacy and data sovereignty concerns.

When choosing a method, your team will see that there is sometimes a tradeoff between a method’s cost and its accuracy and reliability. The key is to select the most cost-effective method that will ensure your data are accurate and reliable enough to meet your management needs. Depending on your needs, you may not have to collect primary data, but instead could take advantage of existing data. For example, one method for getting data about a given fish population would be to download harvest records posted by a government agency on the internet. In some instances, however, primary data collection will be required.

It is helpful to document the specific protocols you use to implement your methods. Doing so will help in data interpretation, as well as future monitoring of the same indicators to detect patterns over time. Ideally, your team should test and adjust indicators and methods before using them. For example, you should pilot survey instruments to ensure they give you the data you need and are not subject to misinterpretation. Likewise, collecting baseline data early on could help you test your methods. If you cannot establish baselines within the first few months of a project, then most likely you need to review the methods or the indicators.

Monitoring Plan - Pulling It All Together

Your audiences, information needs, indicators, and methods are all part of your monitoring plan. Your plan should also specify roughly when, where, and by whom data will be collected (see Figure 10 for an example monitoring plan). As you develop your monitoring plan, consider how the data collection process may impact interested parties and how that information will be stored (addressing any privacy or data sovereignty concerns). As part of your work planning and budgeting (Step 3), your team should include time and financial resources to support monitoring activities and data management.

Finally, and in preparation for Steps 3 (Implement) and 4 (Analyze & Adapt), your team should consider protocols for how you will manage and access data and how you anticipate analyzing and using data to meet the information needs of your key audiences. Incorporating information on your indicators, methods, and supporting data into a structured system that links your actions to your results, goals, and objectives will facilitate your team’s ability to synthesize across all of this information. Additionally, thinking ahead to Step 5 (Share), it’s also useful for your team to begin planning for the creation of public data repositories with clear data collection and management protocols so that others can understand, use, and reproduce them.

Figure 10:Extract of a monitoring plan for promoting climate-smart urban approaches.

2B OUTPUTS

- Audiences and their information needs and preferred communication modes clearly defined

- Indicators and methods identified

- Finalized monitoring, evaluation, and learning plan

2C. Develop Operational Plan¶

Conservation projects are ultimately implemented by people and institutions. Even the best strategic plans and monitoring plans are of little utility if you cannot put them into operation. With this in mind, this sub step involves developing an operational plan for your project. Key components of an operational plan include analyses of:

Human capacity, skills, and other non-inancial resources required to implement your project and what you need to do to develop those resources, including cultivating partnerships. You can use your theories of change and activities to develop high-level time estimates and to identify the skills required to implement your actions and the associated monitoring activities. It is also useful to refer back to your early work on identifying your team and the key skills and skill gaps within your team.

Funding required to implement your project and an accounting of your current and potential sources of these funds. To identify the funding needed, your team should develop broad estimates using your analyses of human capacity, skills, and other resources. Be sure you include any major equipment expenses (e.g., vehicles). Again, your theories of change will provide a good framework for making those high-level estimates.

Risk factors of concern for your project and how they can be addressed. A risk factor is an uncertain event or condition which, if it occurs, has a negative effect on at least one project element (e.g., time, cost, scope, or quality). Risks can be subdivided into programmatic risks that affect your situation (e.g., political instability, drought) and operational risks that affect your ability to implement the project (e.g., change in organizational leadership, limited capacity of partners). A risk assessment should rate both the probability of the risk factor occurring and the impact or severity of the risk factor if it does occur. The purpose of a risk assessment is to identify issues that could negatively impact the project’s ability to implement key actions effectively and/or achieve conservation goals, including any impacts on rights holders and other interested parties. A risk assessment also identifies additional actions necessary to mitigate or avoid those risks. As such, a risk assessment is an important input for action selection (Step 2A). A risk assessment template (defined by your organization, if relevant) is useful to document and rate your risks, prioritize your efforts, and re-rate the risks as your project evolves.

Social safeguards your team has in place to protect individuals and communities from adverse impacts. These safeguards aim to ensure that the rights, wellbeing, and interests of vulnerable or marginalized groups are respected and protected. Some examples of social safeguard mechanisms include free prior and informed consent (FPIC) for Indigenous communities, grievance redress mechanisms, and training for staff on ethical practices;

Transition strategy to clarify how long your project will last and how you will ensure the sustainability of your project’s achievements beyond your team’s involvement. While we include this element under the operational plan sub step, it is important to consider sustainability and transition options at the start of your project. Doing so helps ensure that associated actions are included in your work plan and can be adapted as your project evolves. Ignoring these factors can lead to unrealistic expectations among the project team and interested parties, which can become increasingly difficult to manage over time.

The first two components of an operational plan technically form the basis for a (high level) work plan and budget, both of which are covered more thoroughly under Step 3. The level of detail and formality of your operational plan will vary, depending on the size and complexity of your project. Small projects may only briefly touch on each of these topics, whereas large, complex ones might have an extensive and formal treatment of each.

At the conclusion of the Plan Step, you will now have most of the products of a conservation plan (Figure 1). Depending on your needs, you may want to compile this information into a formal plan. Or, if you are using software like Miradi, you can maintain this information in the software and produce the relevant plans and documentation as needed. This creates a “living” plan that can be updated easily as your project evolves. It also enables ongoing linkage of data, such as budgets, with other organizational systems.

2C OUTPUTS

- Assessment of human, financial, and other resources

- Risk assessment and mitigation actions

- Social safeguards

- Estimate of project lifespan and transition strategy

PLAN RESOURCES

CS Library Resources: Filter by “Plan” and then search within, if desired, by guidance, case studies, or other search terms

Recipes for Conservation: A Conservation Standards Toolkit: Navigate to the relevant Tipsheets in the Recipe Toolkit, as well as the Plan sections in the Examples & Resources document

Real-world Examples of Applications of the Conservation Standards

In CS 5.0, we have substituted the term “action” for the previously used term “strategy” to better fit how the rest of the world uses these terms. An action is now a component of a broader strategy.

While some people think that results chains are the same as logical frameworks (logframes) or logic models, they differ in important ways. Logframes provide a simple way of organizing goals and objectives, but, unlike results chains, they do not explicitly link actions, objectives, and goals. Logic models are more similar to results chains, but results chains have the flexibility to show more detail, branching, and the direct relationship between one result and another.