In this important step, your team will use project management principles to put into action the planning work you did in Steps 1 and 2. Step 3 involves developing and implementing specific work plans (Figure 1, Plan Chapter), while ensuring sufficient resources (people, equipment, and funding), skills, knowledge, and partners. All of this work should be done within the context of the implementing team’s organizational policies and procedures and decision making processes for approving work plans and budgets. As you move into implementation, don’t aim for perfection or wait for all the pieces to be in place. Work plans (and strategic plans) evolve over time.

3A. Revisit Team Structure & Process¶

Likewise, even teams evolve over time. Sometimes, those implementing a project have not been involved in all steps of the planning process. The Implement Step is a good point to revisit your team and supporting staff (e.g., finance, fundraising, and communications) to ensure you have the right mix of staff and partners to support implementation and/ or provide expertise missing from the current team.

The monitoring plan developed in Step 2 should have identified the key audiences and their information needs, but as you build your work plan, think about any additional people or groups that can influence the successful implementation of your project. It is important to build communications activities into your work plan. You even may wish to develop a dedicated communications strategy to stay on top of communications throughout your project’s lifecycle.

At this step, you should revisit or create a team charter or other partnership agreements (see Step 1) to establish roles and responsibilities for different organizations and individuals. If you have not already done so, now is an important time to carry out due diligence on potential partners. As you revisit your team structure, make sure you have a clear project lead who will coordinate and keep the team focused and moving forward. Consider developing team norms to ensure all team members are in agreement about the work and how it will be conducted. Your team norms should cover procedural equity so that all team members and interested parties are treated equitably.

This concept should be incorporated in how the team functions, as well as how the work is implemented. If your project is likely to continue over many years, you will want to consider how the team will deal with succession planning. For example, you should be documenting your decisions and progress, so that you can more easily bring new team members on board.

3A OUTPUTS

- Updated team charter and other partnership agreements, as relevant

- Updated communications strategy stating how you will keep interested parties engaged as to your progress

3B. Develop Work Plan & Timeline¶

In the previous steps of the Conservation Standards cycle, your team developed your strategic plan, monitoring plan, and operational plan (Figure 1, Plan Chapter). In this step, you need to turn these general plans into more specific ones and then implement them on an ongoing basis.

The first part of this step is, with your project team and partners, to work from your strategic plan (in particular, the goals, objectives, and theories of change) and your operational plan to develop a more specific short-term work plan covering the next few months or, at most, year. While elements of a work plan often vary by team or organization, any work plan should include at least the following:

The specific activities and tasks required to implement the actions laid out in your strategic plan. In addition to the programmatic activities, make sure your work plan includes what you need to do to:

- coordinate your project (e.g., organizing attending weekly meetings, developing partnerships, engaging interested parties, finalizing an FPIC process);

- monitor progress and or key uncertainties;

- implement your operational plan (e.g., communications, fundraising, conflict resolution activities);

- review and update assessments (e.g., situation analysis, risk assessment, interested parties assessment);

- analyze progress and adapt; and

- share project updates with interested parties.

Who will be responsible and who will be accountable for completing each activity and task, keeping in mind any barriers, power dynamics, or social biases that may influence an individual’s ability to fulfill the role. In complex and/or collaborative projects, it is particularly helpful to name the role and the person/ organization to clarify expectations and establish accountability. In doing so, it can be helpful to use standard categories, such as RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) or MOCHA (Manager, Owner, Consultant, Helper, Approver).

When each activity will be undertaken and the sequence of associated linked activities and tasks. Consider the timeframe stated in your goals and objectives when deciding how soon you need to implement activities in your work plan.

Where the activity will happen, in those cases where some activities are relevant only to specific areas.

Your organization or team charter might have guidance for the timeframe to be covered by your work plan, but generally, you should develop detailed work plans for the next 3-12 months, with higher-level information for the longer term. As time moves on, you can take your higher level estimates and refine them into more specific estimates to reflect the timeframe for your goals and objectives.

Your detailed work plan will provide you with the basis for developing a project timeline or calendar. It is important to develop your timeline so that all project team members budget their time according to the project needs. Your work plan will also help you identify which team members might have time and which are overbooked. If any team members are over-allocated, it is essential to address this by redistributing (within your team or to a partner), delaying, and/or cutting back on certain activities.

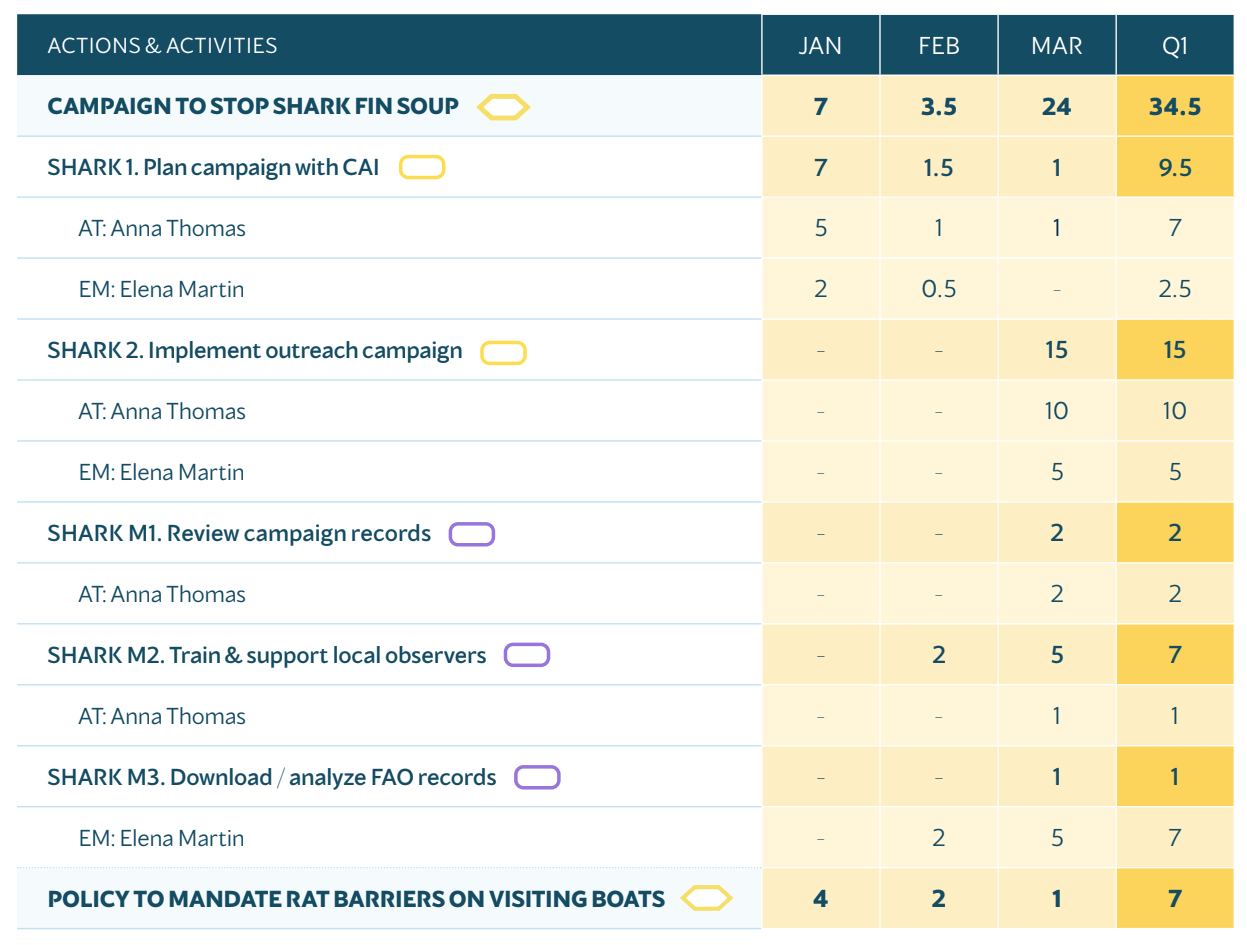

As your project moves along, you should revisit the project assumptions in your theories of change and update your work plan regularly, again focusing on the more detailed activities for the next few months. Figure 1 shows an example of a table with people assigned to work on the project’s actions and monitoring activities.

More generally, it is important to make sure your team has a system for documenting your work planning and tracking implementation (e.g., work planning software, spreadsheet, project calendar). Whichever work planning tool you use should allow you to easily adapt your work plan to changing circumstances.

Also, you may need to share your implementation progress outside of your team and should choose a system that will allow you to easily develop relevant reports for key audiences (e.g., funders, the project team, partners). Automated dashboards can be very effective in showing implementation progress.

Figure 1:Work plan extract for a marine site, showing Assignment of people and work units. Key: Yellow hexagon = action, yellow oval = activity, and purple oval = monitoring activity.

3B OUTPUTS

- Work plan detailing the activities, tasks, and responsibilities associated with your strategic, monitoring, and operational plans

- Project timeline or calendar

3C. Develop and Refine Budget¶

Your work plan is a critical input for developing a project budget. You should now have a clear decision of the actions, activities, and tasks you need to undertake and so will be in a good position to determine the time and financial resources you need to successfully implement your strategic plan. As a starting point, you should use your initial analysis of funding required that you developed in your operational plan (Step 2C). This, along with your strategic plan and your work plan, will help you develop a more refined estimate of costs for specific activities and the broader actions and strategies into which those feed.

It is important to work closely with the finance or accounting staff in your organization (if relevant) to develop your project budget. For many projects, your most expensive resource needs will be staff time. In addition, you should consider what other major expenses (e.g., equipment, travel costs, goods and services) are needed. It is helpful to look across your activities to make sure you have considered non-staff costs associated with them. You will also want to consider the related functions or additional resources the project might require, ranging from monitoring, management, and safeguards expenses to administrative or logistical support and capacity development. In developing your project budget, you should also ensure you have considered any costs associated with accessibility and volunteer activities (e.g., transportation, meals).

When you are working on a project with multiple organizations, agencies, and/or countries, budgeting can look very different. In such situations, your approach to budgeting may be shaped by the requirements of the funder or other overseeing entity. Which budgeting system you use will also depend on the context of your project. For simpler projects, a spreadsheet may be sufficient. For more complex projects, tools like Miradi provide features to link your strategic plan and work plan to your budget. With tools like this, you can easily identify any tasks or items in your work plan that lack funding, ensuring a clearer view of key financial gaps in your project.

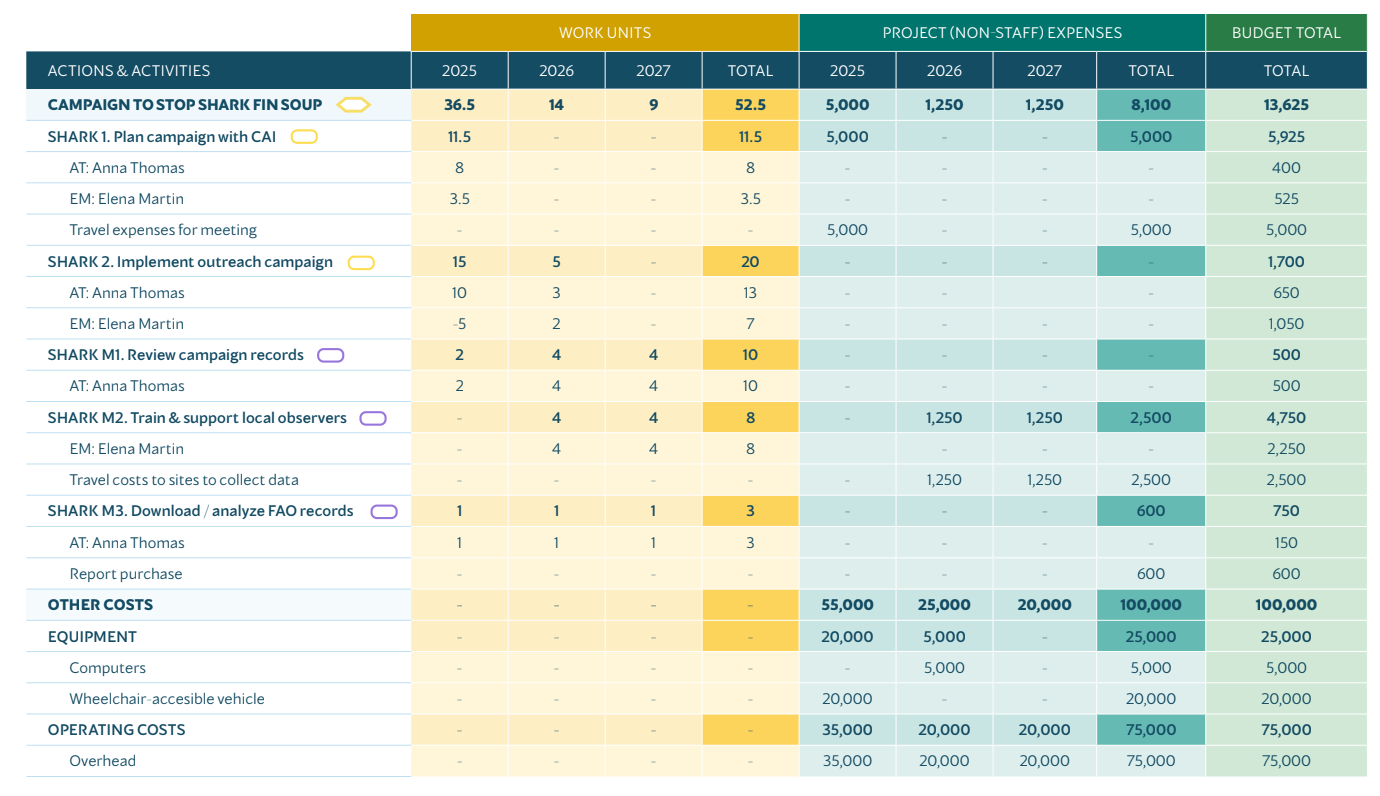

Figure 2 shows the work plan from Figure 1, now expanded to include the expenses necessary to implement the project’s actions and monitoring activities. Non staff expenses are combined with the cost of time for the assigned people to create the total budget for each item. In this example, staff and expenses roll up to show the costs for an activity, all activity costs associated with an action, and all actions within each of the project’s strategies. The project budget also outlines other expenses, including equipment and general operating costs not directly associated with implementing a specific action or activity.

Figure 2:Work plan extract expanded to include expense details and others costs. Key: Yellow hexagon = action, yellow oval = activity, and purple oval = monitoring activity.

Once you have developed your project budget, you will likely need to identify potential funding sources and submit proposals. The information collated in your strategic plan and work plan should be used to develop robust funding proposals. Most projects require several years of financial resources, so fundraising is often an ongoing process as you move through different iterations of the project cycle. Indeed, it can be useful to develop a fundraising strategy and where relevant, clarify with your partners whether fundraising is done jointly or separately by each partner.

In addition to using the strategic plan to inform funding proposals, you can incorporate ongoing results and lessons learned into your proposals and reports to show donors the progress, learning, and adaptation taking place. This provides an opportunity to help donors understand the value of supporting – teams that use a Conservation Standards approach from the strategic decision making that informs the design and planning (including clear approaches to measure progress and impact) to the critical thinking and reflection that go into the monitoring, analysis, and adaptation. Moreover, many funders request specific elements, such as theories of change, in proposals. Using a CS approach puts your team in a good position to meet these funder requirements.

Ideally, you would seek and acquire funding for your highest priority actions from the start. In reality, you may need to adjust to opportunities and constraints and may find that your initial funding focuses on some medium- or lower-priority actions. That’s fine, as long as you do not lose sight of your high priority actions, and you work to implement them as soon as feasible. This is a good point to reflect on whether it is probable you will be able to meet your project goals and objectives in the anticipated timeframe and with the likely staff and financial resources. You may need to make some important decisions about your project, including whether you need to eliminate, postpone, or scale back any of your actions, activities, or tasks or potentially pass them off to a capable partner. You should also reflect on the adaptations you might need to make and determine whether your overall project can still be effective and if it makes sense to continue forward.

3C OUTPUTS

- Project budget

- List of potential funding sources

- Funding proposals developed and submitted

3D. Implement Plans¶

Implementing your project involves putting your strategic, monitoring, and operational plans into action and ideally, according to schedule and within budget. To start, it is beneficial to have an initial meeting for the project team (especially if there are new people). This is an opportunity for team building and to ensure all team members are familiar with the project design, team charter, budget allocations, donor contractual conditions, internal policies, and other relevant details. It is also a good time to review how internal decisions are made and how the project will address conflicts that may arise. Your communications strategy can help your team have a clear understanding of how everyone will communicate about the project internally and how you will report outcomes and progress to the public.

You should aim to directly engage team members responsible for implementing your project from the start and repeat these team meetings at regular intervals. Doing so helps your team to routinely monitor progress, plan upcoming priorities, stay connected, solve problems together, and support one another. These meetings should also serve as a space to implement Steps 4 (Analyze and Adapt) and 5 (Share) on a regular basis.

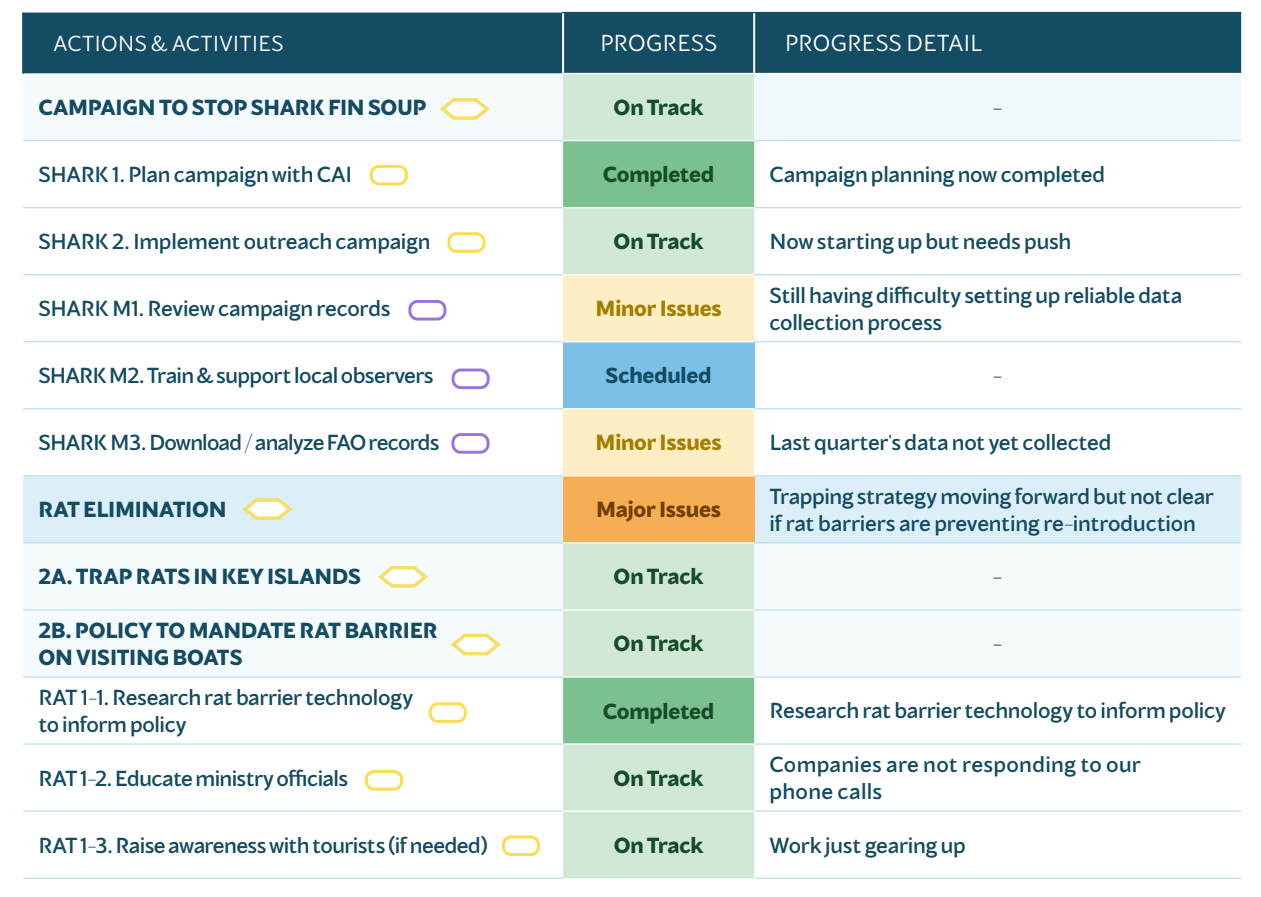

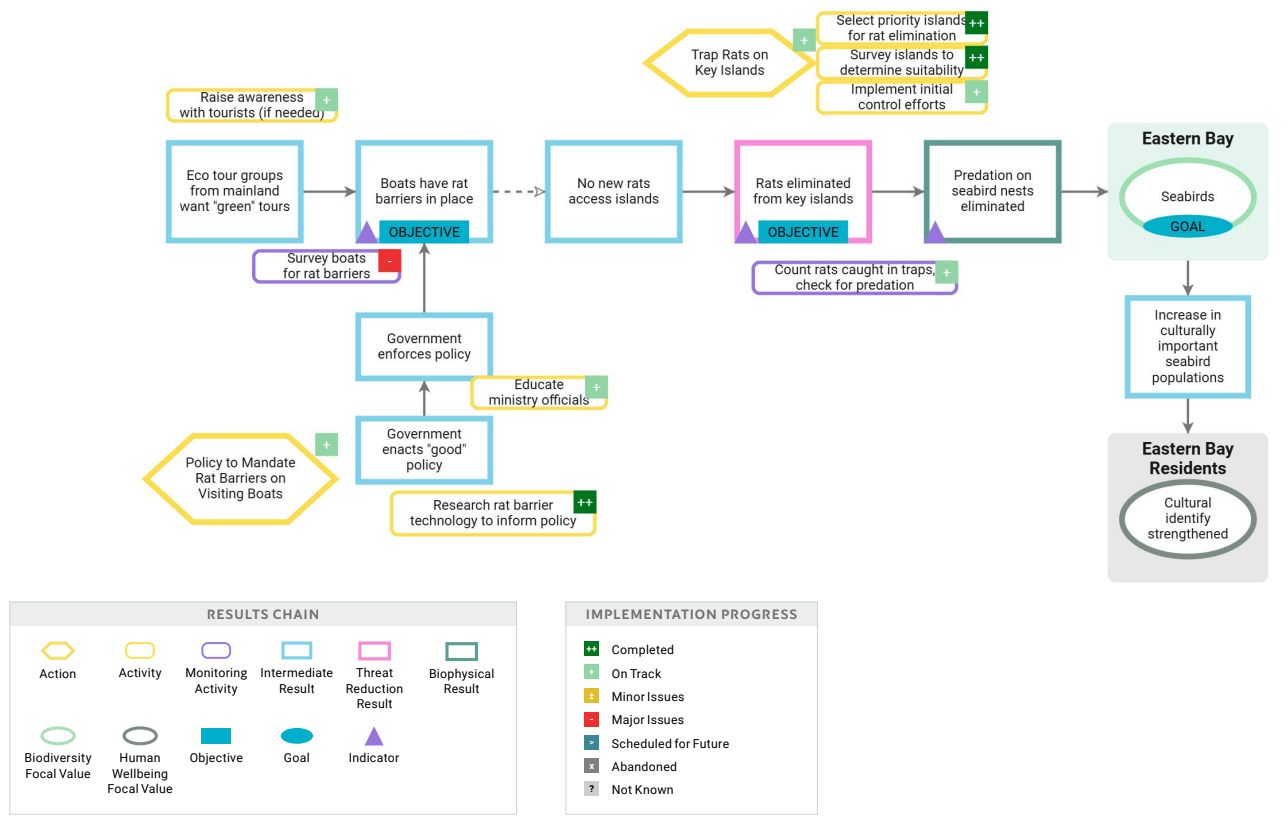

To monitor your implementation (e.g., progress on activities, finances, risk management, and social safeguards), it can be useful to use progress tracking tools. Creating short, regular progress reports about implementation will allow more detailed reflections in the later steps, as well as assist with reporting to donors and supporters. At least annually, it is important to look at your progress in the context of your theory of change (Step 4B provides more detail). Figure 3 and Figure 4 provide different formats for reporting progress on actions that may resonate with different audiences.

Figure 3:Example of progress reporting in table format. Key: Yellow hexagon = action, yellow oval = activity, and purple oval = monitoring activity.

Figure 4:Example activity progress report in results chains diagram.

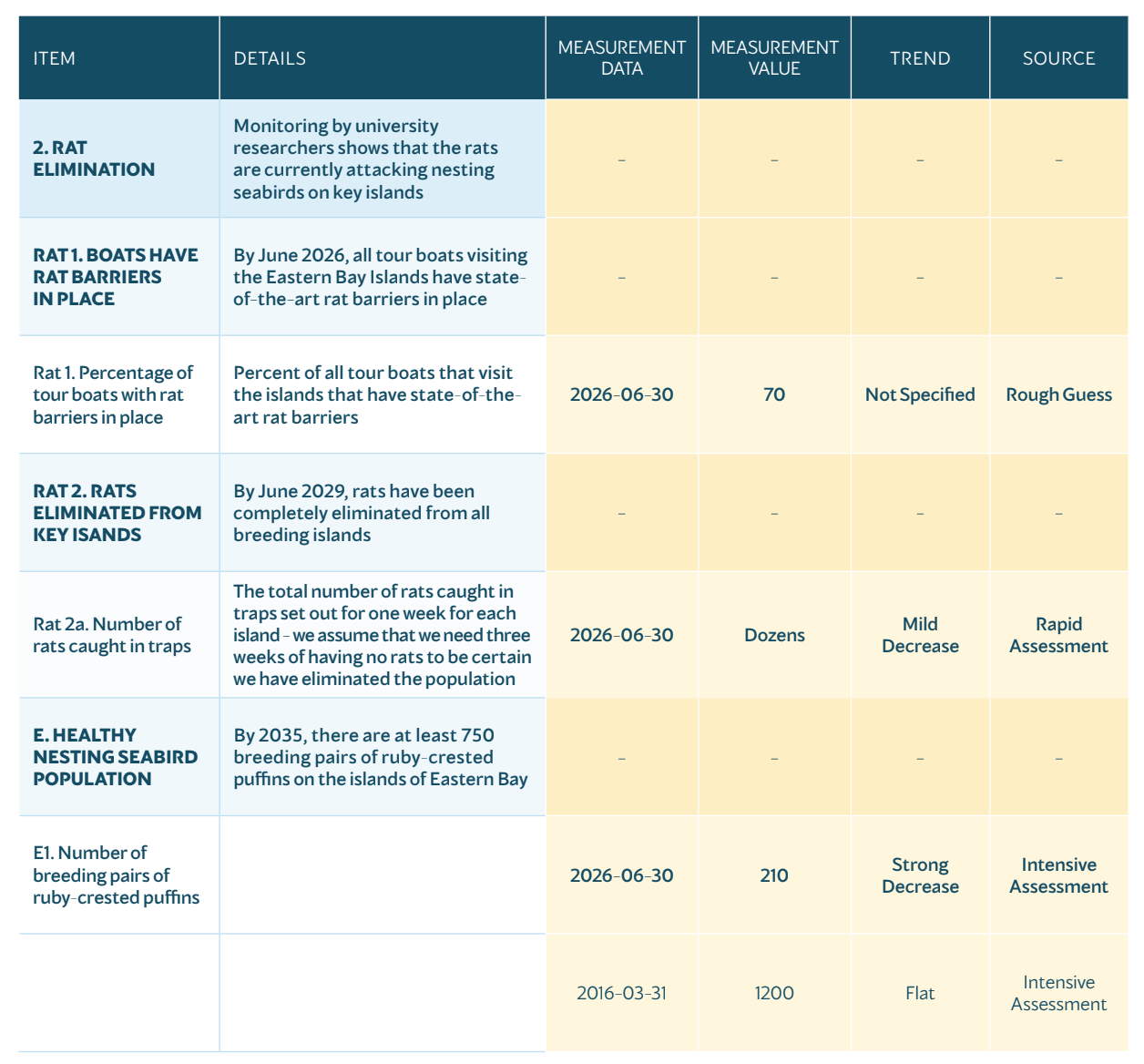

As your team collects monitoring data (related to implementation, results, and other information needs), it is important to ensure you have systems to support data collection, storage, and access for future analyses. This is a good time to again consider data ownership and sovereignty, privacy, and accessibility by interested parties. In terms of accessibility, a simple paper - or desktop-based system may be adequate for very small projects. For more complex projects, you may need to work with multiple departments within your organization and/or with partners to standardize monitoring data flows, ensure the data systems you use will integrate with existing systems, and identify any needed adjustments. As a reminder, you will want to include time and resources in your work plan and budget for setting up these systems. Prior to moving to Step 4 (Analyze & Adapt), it is useful to ensure your data are collated, complete, and accurate and that they can be easily accessed and manipulated. Figure 5 shows an example of monitoring data for a few indicators from the Rat Elimination strategy.

Figure 5:Example of monitoring data

3D OUTPUTS

- Implementation of strategic, monitoring, and operational plans (as outlined in your work plan), keeping in mind your project budget and schedule

- Systems for storing and accessing data - Monitoring data captured in systems

- Implementation progress reports to your organization, funders, and other interested parties

IMPLEMENT RESOURCES

CS Library Resources: Filter by “Implement” and then search within, if desired, by guidance, case studies, or other search terms

Recipes for Conservation: A Conservation Standards Toolkit: Navigate to the relevant Tipsheets in the Recipe Toolkit, as well as the Implement sections in the Examples & Resources document

Real-world Examples of Applications of the Conservation Standards