This step in the Conservation Standards cycle involves specifying the basic parameters for your project and assessing your overall context. In particular, it involves determining the purpose of your team’s planning process and identifying who will be part of your project team initially and who should be involved in other ways. It also involves articulating your project’s geographic and/or thematic scope, your vision of what you hope to achieve, and the focal values you are prioritizing. Finally, it includes making sense of your project’s context, including identifying threats, opportunities, and key constituencies interested in or impacted by the project.

1A. Define Purpose & Identify Team¶

Define Purpose of Conservation Standards Work

You can enter the Conservation Standards cycle at any point in the process.[5] Wherever you enter, you should start by being clear about why you are using the Conservation Standards and how you think they will support your team (e.g., develop a full strategic plan, reflect on effectiveness of work to date). This includes clarifying the specific decisions, decision makers, and people the CS process will impact positively and/or negatively. As part of this review, you may find it useful to revisit your organization’s mission and current priorities to help clarify decisions already made, decision maker expectations, and assumptions about funding and other resources. If you are collaborating with partners, you should also compare your respective missions and priorities at the outset and identify where your needs and values are compatible, as well as where there may be tension or conflict. Likewise, if you expect to work with a specific donor, you may want to encourage the use of the Conservation Standards as the primary process, or at least crosswalk terms and steps to increase understanding.

As relevant, you should also draw on what you and others have learned from earlier iterations of your project and/or similar projects. This review will help you determine how much effort you should invest in this process and which steps are relatively more important than others. For example, if focal values and goals have already been identified and a threat assessment exists, then you may be able to review them and move on to developing your situation analysis and strategies.

Project Team

Your project team is the group of individuals who design and implement your work. Team members often include people from your organization, as well as key partners and interested parties . Interested parties include key partners and other individuals, groups, or institutions that have a vested interest in or can influence the project and/or that may be affected by project activities and have something to gain or lose. It is important to think about how to involve a variety of interested parties, as your plan and its acceptance depend heavily on who is included in the team. Teams typically have a project leader who is responsible for the overall coordination and moving the team forward. Some organizations also have a higher level manager to whom the team reports. In general, it is important to be clear about all team member roles and responsibilities. It is helpful to formalize these and

In forming your team, it is important to understand the skills and experience needed and recognize who would bring those skills and where you may have gaps that you need to fill. In addition to the technical or programmatic expertise, many teams need access to administrative, financial, and communications skills. The team composition may change as you move through the CS cycle and as your project needs change or evolve.

As you form your team, procedural equity is important to consider. This might involve reviewing existing power dynamics, seeking representation from relevant actors, and documenting your decisionmaking process. Different groups will likely have different expectations around decision making, so it is important to work together to clarify this early on.

You may also wish to identify one or more advisors to whom your team can turn to honest counsel. Ideally, these are influential people with the ability to positively affect your work. Once you understand the network of interested parties, it is helpful to revisit whether any of these individuals should be part of your project team and, if so, determine how they might overcome any barriers to participation (if relevant).

1A OUTPUTS

- Identification of purpose, decision makers, decision-making process, and decisions needed

- Identification and engagement of interested parties and support for their participation where barriers exist

- Selection of initial project team, including project leader, core members, and advisory members

- Identification of existing skills among team members and key gaps you should fill

- Designation of roles and responsibilities

1B. Define Scope, Vision, & Focal Values¶

Scope

Before you think about what actions you will implement, you should have a good understanding of what you broadly hope to accomplish, as this will help determine your scope and be the foundation of all your planning work. A project’s scope defines what the project intends to affect but does not necessarily limit where actions that affect the scope take place. There are three common options:

Place based scopes have a geographic focus and include efforts to conserve or manage ecoregions, ecosystems, priority areas, or protected areas. An example of a place based scope is a national park, encompassing the different ecosystems and biodiversity contained within the park boundaries.

Focal value based scopes center on specific species or ecosystems. Species based scopes may also include a part or all of the species’ life history across relevant geographies. An example of a species based scope is a global tiger program, focusing on tigers across multiple landscapes that offer the best chance of growing the population. Examples of an ecosystem based scope include mangroves in Asia or global grasslands.

Thematic based scopes focus on efforts to address specific threats, opportunities, or enabling conditions. Examples of a thematic based scope include a project focused on illegal logging that aims to reduce timber imported into the European Union or a climate program that seeks to decrease national CO 2 emissions from transportation, homes, food, and energy production.

Box 4 WHAT IS BEHAVIOR CHANGE AND WHY DOES IT MATTER?

Conservation challenges are often behavioral challenges. To solve them, it is important to consider how human behaviors at all levels of a system can support, scale, or block progress to your conservation goals. Behavior change is the process of changing what people do - i.e., increasing, maintaining, or decreasing a current behavior, or adopting a new behavior. When seeking to change behavior, it is key to understand the unique social, cultural, political, and economic contexts and systems in which these behaviors occur. This includes understanding whether your goals align with the goals of key actors and interested parties, reflecting on your biases and power dynamics about “right” behaviors, and considering the potential to do harm instead of good. Behavior change activities should be transparent and inclusive and follow ethical guidelines for research, engagement, communication, and evaluation.

In projects with a geographic footprint (and even those that focus on a theme), it is often helpful to develop a spatial map that includes key conservation management units, landscapes, ecological features, and/or sociopolitical boundaries. Doing so may help you identify the need to consider additional partners, focal values, and threats within the project area. Regardless of the scope you define, addressing conservation challenges almost always necessitates understanding, changing, and/or amplifying human behavior at one or more levels (Box 4). You will need to think about the appropriate scale to achieve the desired impact (e.g., you may need to work across multiple protected area projects that contribute to an overall protected area network). You should also think about the temporal dimension of your work, which will influence how much you can achieve. In many cases, a one year or five year project is not going to significantly alter the viability of an ecosystem or species. But, it may influence human behaviors or policy changes that could ultimately affect ecosystem or species viability.

Given the dynamic roles humans play in conservation outcomes, it is common for teams to incorporate human wellbeing when developing their conservation projects. While addressing human wellbeing alongside conservation efforts is ideal, it often comes with different skill sets and resource needs. It is important to recognize this and clearly define what falls inside and outside the scope of the project.

Vision

In addition to defining the scope, it is also necessary to decide on a clear and common vision – a description of the desired state or ultimate condition that you are working to achieve. You can summarize your vision in a vision statement, which meets the criteria of being relatively general, visionary, and brief (see Annex 2 for descriptions of these criteria). A project’s vision should also consider the context of your organization’s mission and the needs and interests of other parties within your project scope.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 1: SCOPE AND VISION

In defining your scope, consider if you are focusing on biodiversity conservation and need to take into account how climate change will affect your biodiversity focal values and/or if you are focusing on reducing the impact of climate change on humans by protecting and restoring ecosystems (i.e., ecosystem-based adaptation). You should also consider whether one of the primary aims of your project is to avoid, reduce, or sequester greenhouse gas emissions, using nature-based solutions.

These high-level decisions could influence your geographic scope. You should think beyond today and consider both how climate has changed and how it is likely to continue to change, including whether ecosystems or species ranges are likely to shift (latitudinally or altitudinally) or the distribution of species within an ecosystem is likely to change. It is also important to consider future human needs and responses to climate change.

Your vision should be forward looking, describing a future ecological state that takes into account projected climate conditions. Given these projections, you may need to define your future ecological state not only in terms of composition and abundance, but also in terms of ecosystem structure, function, and processes.

Focal Values

A focal value is what a project seeks to ultimately affect. It is often an element chosen to represent key aspects of the overall system. Types of focal values include biodiversity values (e.g., species, habitats, or ecosystems), climate values, cultural values, and human wellbeing values. In CS 5.0, we are substituting the term “focal value” for the previously used term “target.”

Biodiversity Focal Values

Once your team is clear on your project scope, you should select a limited number of biodiversity focal values (also known as ecological focal values).[6] These focal values are specific, tangible entities that your project is working to conserve and that represent and encompass the ultimate aims of the project. They form the basis for setting goals, selecting actions, and measuring impact. The specificity of biodiversity focal values will vary with the scope or type of project:

For projects with a place or focal value based scope, biodiversity focal values are ecological systems, habitats, and/or specific species chosen to represent and encompass the full suite of biodiversity within the scope. For a place-based scope, conservation of the chosen suite of focal values should, in theory, ensure the conservation of all ecosystems and species within the project scope. Most place based projects can be reasonably well defined by eight or fewer well chosen biodiversity focal values. Larger scale place based projects may require either a few more focal values or coarser focal values (e.g., an assemblage of species, rather than a specific species). Projects may also focus on a single biodiversity focal value, such as an iconic flagship species (e.g., tigers) or an ecosystem (e.g., mangroves).

For projects with a thematic based scope, the main focus is on specific factors related to biodiversity focal values, such as a threat, contributing factor, or ecosystem service. Depending on the context, teams may identify the specific relevant ecosystem features or species they ultimately aim to influence, or they may only more generally identify “biodiversity” or “natural resources” as their biodiversity focal values.

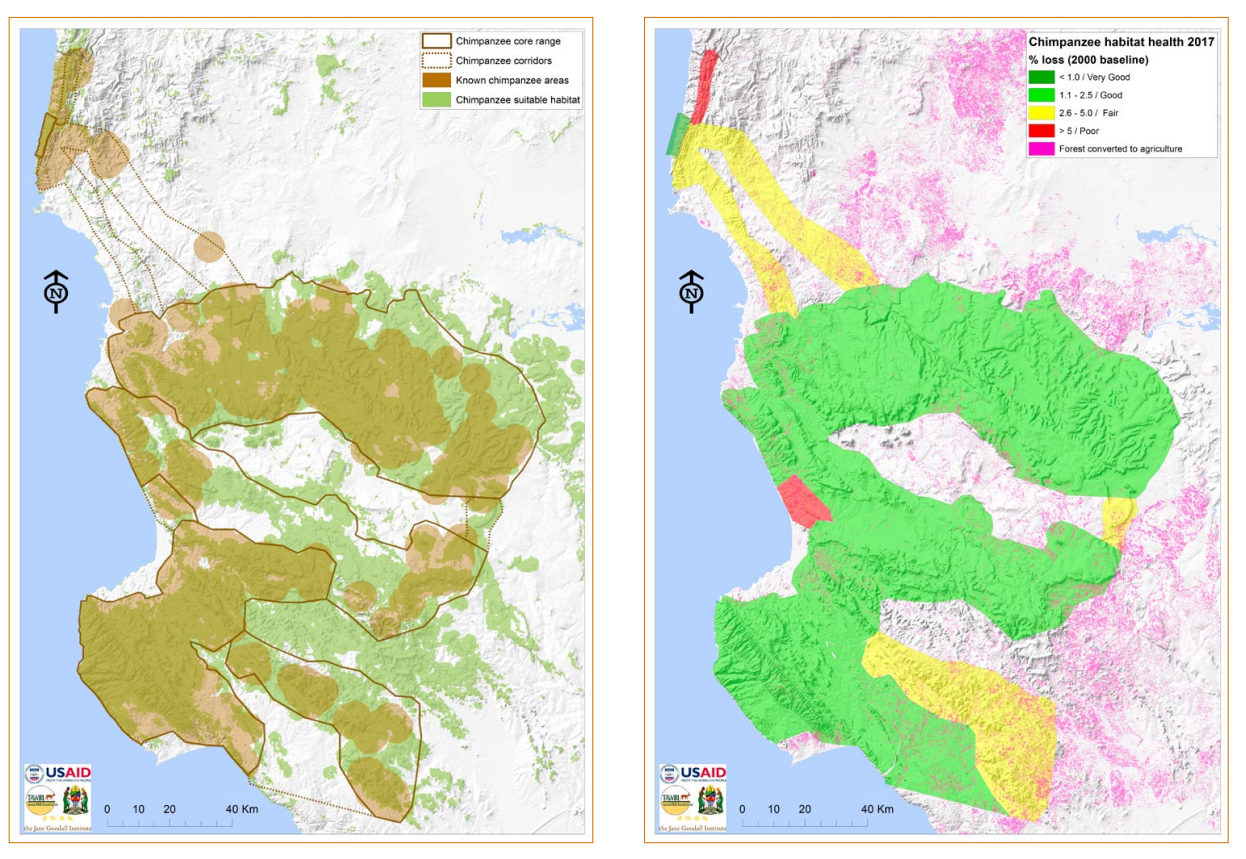

The selection of biodiversity focal values typically requires input from experts across multiple knowledge systems. It is often useful to map the current geographic extent of a focal value, as well as its historic and/or anticipated future extent under different scenarios (Figure 2 in Step 1C provides an example). Moreover, if your biodiversity focal value is wide ranging, (e.g., a migratory species across its range or the full extent of an ecosystem type), it may be useful to divide it into spatially explicit sub-values (e.g., specific populations or life history components, such as breeding, migration, non breeding). Spatial data catalogs may be available for your biodiversity focal values to facilitate this process.

In most cases, you should determine the current status of each biodiversity focal value. At the most basic level, this involves using the best available evidence (e.g., accessing the evidence libraries or consulting traditional ecological knowledge holders) to develop an overall assessment of the health or “viability” of each biodiversity focal value. More detailed status assessments involve specifying key ecological attributes of each biodiversity focal value, determining indicators for each attribute, outlining the acceptable range of variation for each indicator, and determining the current status of the indicator in reference to this range of variation. Many key attributes can be quantified using geospatial indicators (e.g., extent of a habitat, species distribution, connectivity). Geospatial repositories are often good places to find these data. A viability assessment sets the foundation for developing goals for your biodiversity focal values, monitoring focal value status, and understanding key threats to your focal values.

Human Wellbeing Focal Values

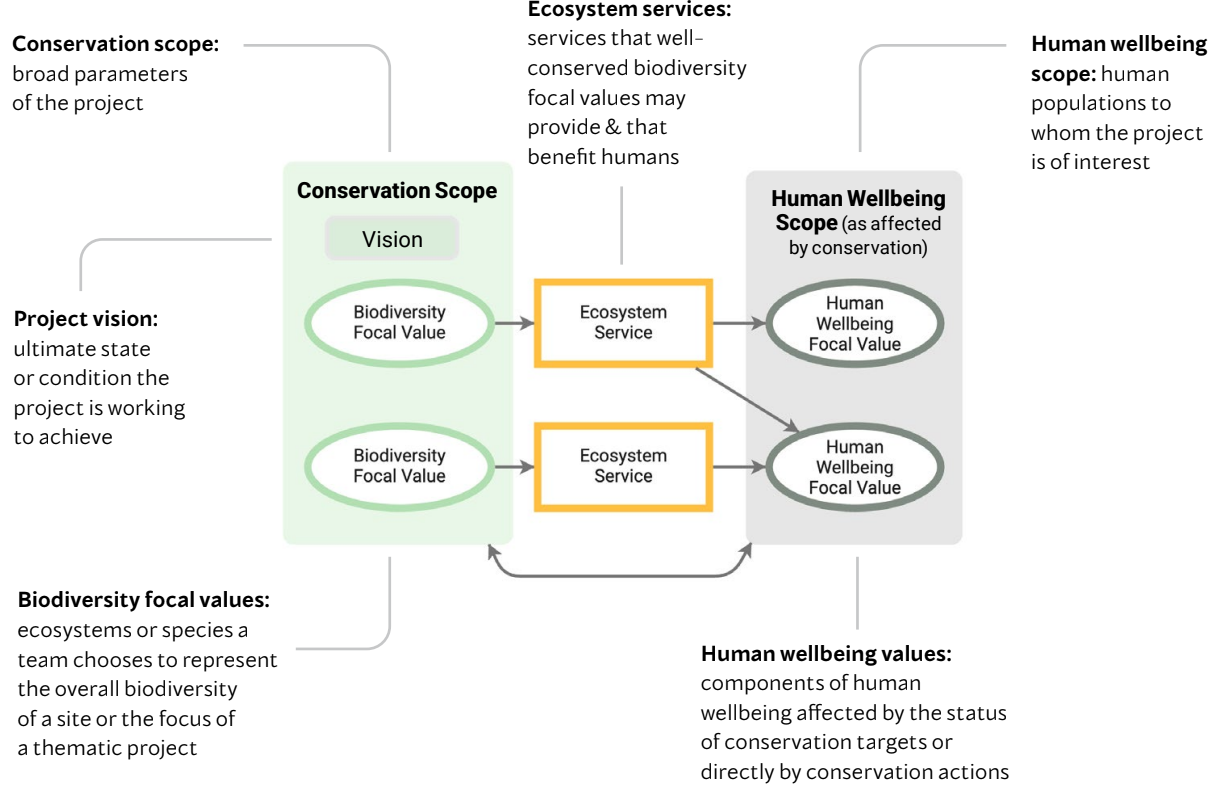

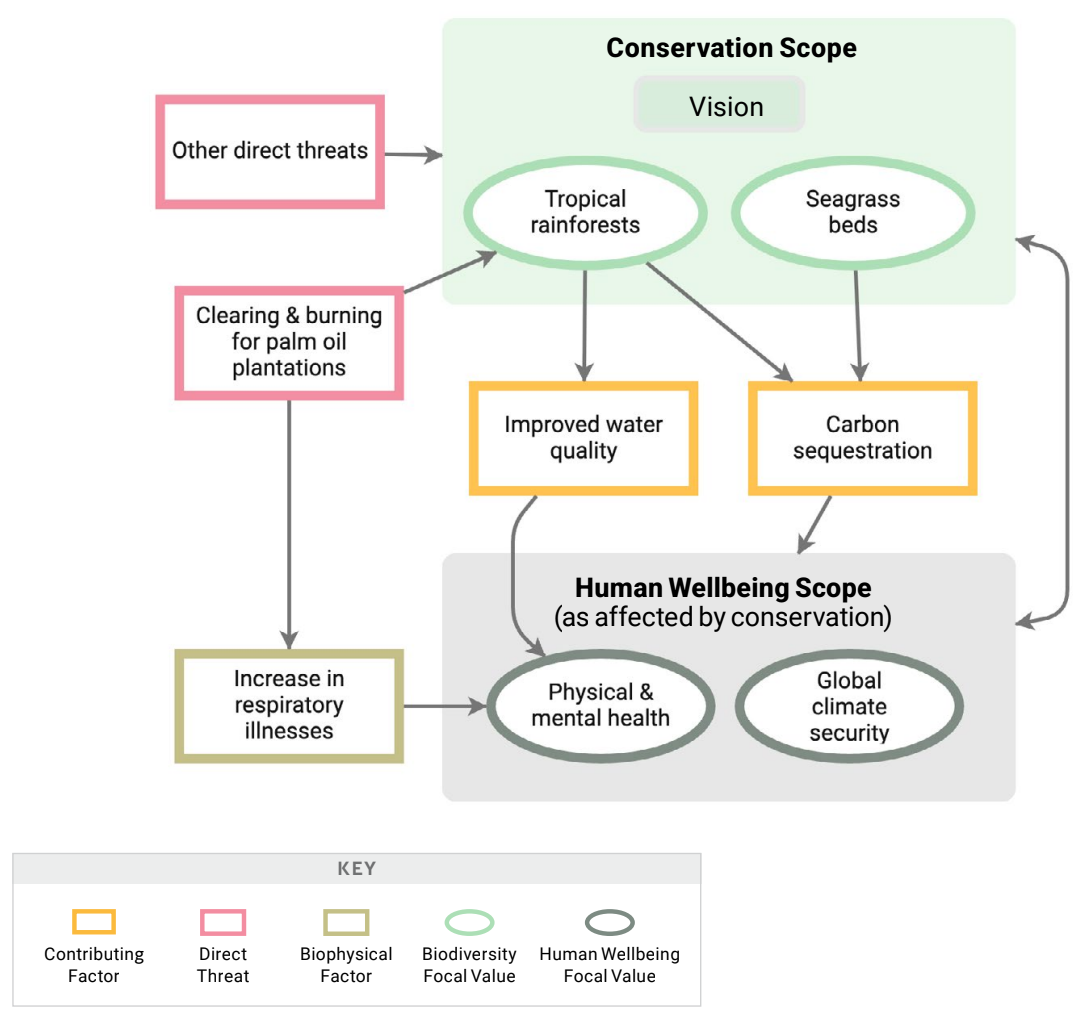

As conservation is inevitably a social undertaking, it is important to show both how humans may impact the outcome of a project and how your work directly affects humans.[7] As part of the process of identifying your focal values and developing your situation model, you should consider including human wellbeing focal values . At this point, your human wellbeing focal values typically encompass those components of human wellbeing affected by the status of biodiversity focal values and associated ecosystem services (Box 5). Examples include physical, mental, and spiritual health, livelihoods and material wellbeing, social relationships, cultural identity, and safety. Figure 1 shows these general relationships, including how biodiversity and human wellbeing focal values may affect one another. Identifying human wellbeing focal values is another place where geospatial approaches can be useful, helping your team visualize and better understand potential ecosystem services and other relevant factors that may impact your human wellbeing focal values.

BOX 5: USING GLOBAL FRAMEWORKS TO HELP FRAME HUMAN WELLBEING LINKAGES

When selecting potential human wellbeing and biodiversity focal values, teams may want to review various global frameworks to better understand their project’s relationship with and contribution to these global initiatives. Many of these frameworks address global challenges and work towards ensuring a more sustainable future by encouraging actions to improve human wellbeing, reduce environmental degradation, and create the conditions to optimize both. There are numerous frameworks that teams can reference, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, United Nations Environment Programme Navigating New Horizons, and IUCN’s Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature, among others.

Figure 1:Generic situation model extract showing scope, vision, and focal values.

As you develop your strategies, you may also want to include human wellbeing focal values that benefit directly from your conservation actions. Conservation efforts often aim to balance biodiversity preservation with human wellbeing enhancement, working to ensure that conservation actions contribute to the long term wellbeing of communities dependent on natural resources. Depending on the team’s primary focus, human wellbeing focal values may be considered independently of, and at the same level as, biodiversity focal values. Note that human wellbeing focal values should always be selected in partnership with the interested parties who will be affected by the work. Regardless of whether your conservation team sets human wellbeing focal values, it is crucial to consider how your work will impact humans, both positively and negatively.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 2: FOCAL VALUES

When you consider the potential impacts of climate change later in the process, you will need to assess:

- whether relevant ecosystems, habitats, and species will remain in your project’s geographic scope for the foreseeable future,

- how climate change might affect each biodiversity and human wellbeing focal value, and

- whether, in light of projected changes, your actions can still be effective at maintaining or improving the status of your focal values.

Once you have done this, we recommend revisiting your scope and focal values. For projects whose primary aim is to avoid, reduce, or sequester greenhouse gases, your team should include as focal values the ecosystems you will conserve, manage, and/or restore to achieve this change in greenhouse gases.

1B OUTPUTS

- Brief description of the project scope, including a map, if appropriate

- Vision statement for the project

- Selection of focal values, including a brief explanation of why they were chosen, and if appropriate, a description and/or map showing each focal value’s location

- Selection of human wellbeing focal values and identification of ecosystem services, as relevant

- Description of the viability status of each priority biodiversity focal value

1C. Identify Critical Threats¶

Once you have settled on your priority biodiversity focal values, you need to use available evidence to identify the direct threats (often called pressures )[8] that influence them and the actors behind those threats. Direct threats are human actions (behaviors) that directly degrade one or more focal values (e.g., unsustainable fishing, oil drilling, dumping of industrial wastewater, or introduction of invasive species). Direct threats can also be natural phenomena altered by human activities (e.g., increase in extreme storms or increase in droughts due to climate change). See the IUCN-CMP Direct Threats Classification for more examples. Where possible, it can be helpful to map the spatial footprint of a threat. Doing so can help you better understand key threats, as well as the drivers behind them (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Simplified spatial maps depicting chimpanzee focal values and threats with chimpanzee habitat focal value (left) and agricultural conversion threat & habitat loss (right). Source: Adapted for Conservation Standards use by Lilian Pintea, Jane Goodall Institute.

When identifying threats, it is important to specify the actors (e.g., specific companies, illegal fishers, poachers). Your team may want to lump or split some threats depending on whether the actors are the same (e.g., you may split “poaching” into “poaching by organized syndicates” and “poaching by villagers”). Being explicit about the actors can assist your team with your interested parties assessment and strategy development.

CLIMATE CHANGE CONSIDERATION 3: ASSESSING CLIMATE THREATS AND THEIR EFFECTS

Climate change can present new threats to a focal value, exacerbate existing conventional (non-climate) threats (e.g., higher temperatures can exacerbate invasive species), and/or interact with conventional threats on the same biophysical factor (e.g., sea level rise and coastal development both reduce coastal wetland habitat connectivity). A biophysical factor is a biotic or abiotic factor that can help clarify how a direct threat affects a focal value. In this example, connectivity is the biophysical factor.

It is important to analyze the potential effects of climate on key species, ecosystems, and people, as well as the indirect effects of people’s reactions to climate change on species and ecosystems (i.e., the effects of maladaptation, such as building sea walls as a response to sea level rise). To do this, identify specific projected changes in climate (climate threats, such as temperature increases, precipitation changes, extreme weather events, ocean acidification, and sea level rise) and how they will affect your focal values, either directly (e.g., higher temperatures and decreased precipitation increases susceptibility to extreme wildfires) or indirectly (e.g., droughts are becoming more frequent so people want to build dams to store water, which negatively impacts freshwater connectivity). Also, identify how climate threats interact with non-climate threats. A climate change vulnerability assessment can be a useful complementary tool, but keep in mind that it focuses solely on climate threats and not on how they interact with conventional threats.

It is important to understand the biophysical effects of climate threats because your focus is likely to be on influencing them, rather than reducing the climate threat. For example, a team cannot change increasing temperature, but after analyzing how it affects ecosystem composition, they could decide to plant drought-tolerant species.

In order to concentrate your actions and resources where they are most needed, it is important to prioritize the direct threats that affect your biodiversity focal values. In particular, you should try to determine your critical threats – the ones that are most important to address. You can use a number of threat rating and ranking tools to help you prioritize. Most tools consider the extent of the threat and the severity of its impacts on the biodiversity focal values. Taken together, these two criteria assess overall threat magnitude. Other frequently used criteria include permanence/ irreversibility and urgency. Some common options for prioritizing threats include: an absolute rating of each threat as it affects different biodiversity focal values, a stress based rating which assesses the effect of stresses (altered key ecological attributes) on focal values and the contribution of different threats to the stresses, and a relative ranking which compares different threats to one another. It is important to consider the entire suite of direct threats and not limit your analysis to the threats your team or organization has the expertise or resources to anticipate and address. Also keep in mind that if an aspect of human wellbeing is particularly important, your team may want to rate the threat to that human wellbeing element. You may need to consider how that threat might differ for human wellbeing versus biodiversity focal values.

1C OUTPUTS

- Identification of direct threats and, if relevant, a map showing the spatial footprint for critical threats as they intersect focal values

- Identification of the biophysical effects of climate threats and interactions among climate and conventional threats - Rating or ranking of direct threats to identify critical threats

1D. Assess the Conservation Situation¶

Situation Analysis

This sub-step builds on work you have already done related to your project context (scope, focal values, and direct threats). These are all elements of a situation analysis that helps your team and partners develop a common understanding of the relationships among the biological environment and the social, economic, political, and institutional systems (and associated actors) that affect your focal values. By understanding the context, behaviors, and key actors, you will be better equipped for designing actions that will achieve your conservation goals and objectives. Depending upon the scale of the project and available resources, a situation analysis can be an in depth, formal study or a less formal description based on input from those familiar with the context. In this sub-step, you should review available evidence, identifying the key contributing factors that drive direct threats and affect the viability of your biodiversity focal values. These include indirect threats (also known as root causes and drivers ), opportunities, and biophysical factors. To the degree that it is feasible and useful, you should identify the actors behind key factors for clarity, and you should keep track of any knowledge gaps.

If your team will be doing more in depth studies, some useful tools include market analyses, political economy analyses, and interested parties assessments. A market analysis can help identify how human behavior responds to economic incentives and how this behavior can adversely affect focal values. A political economy analysis can be a helpful and structured approach to examine power dynamics and economic and social forces that influence development. Likewise, an interested parties assessment can help clarify and differentiate the key actors, their roles, primary interests, level of influence, and opportunity for engagement. It is important to consider both influential parties and those that might be disadvantaged or marginalized. In particular, teams should consider how their process might influence the representation and engagement of different parties in decision making and how that might ultimately affect their wellbeing.

As you do your interested parties assessment, keep in mind which are likely to be important strategic partners for the project (Step 1A), whose behavior you want to affect, and/or whose voice you want to elevate. Whether you want to influence policy making, law enforcement, corporate practice, producer choices, or consumer decisions, all involve attitude and/or behavior change. Having a good understanding of the actors (including their motivations for, barriers to, and local context for behavior change) is crucial to developing a situation analysis and designing effective actions (Step 2A). Additionally, it is essential to ensure rights to obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), so as to protect the rights of communities in any decision making that will impact their livelihoods, lands, or natural resources.

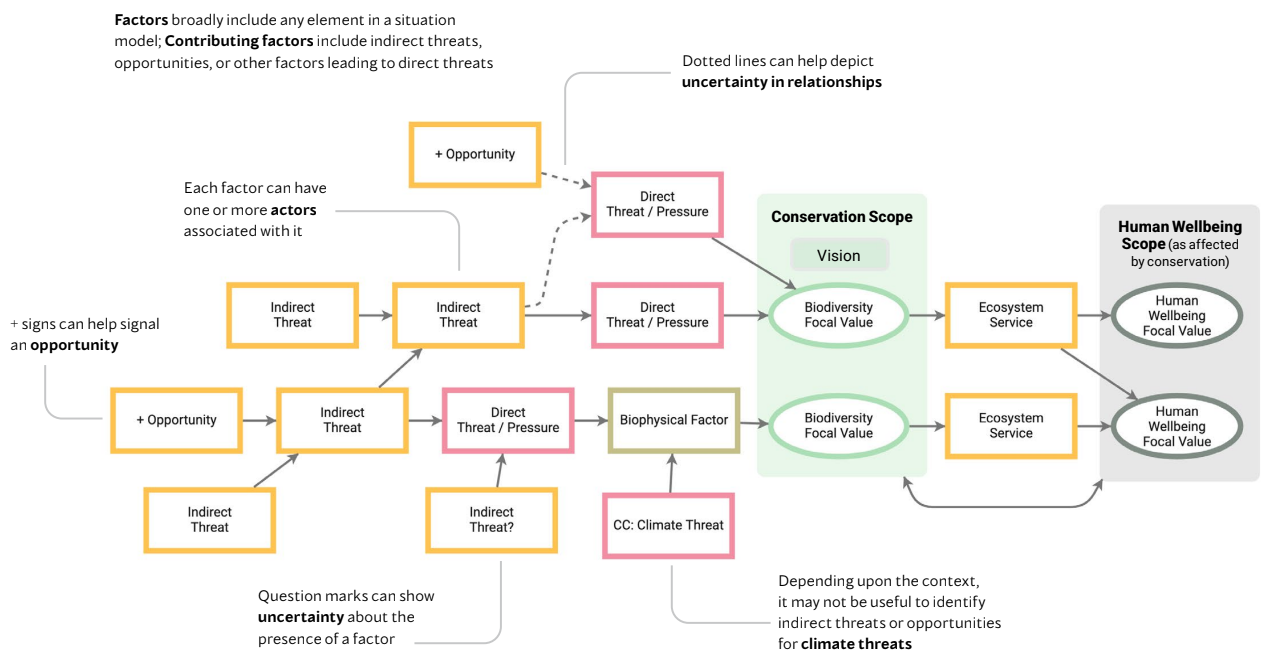

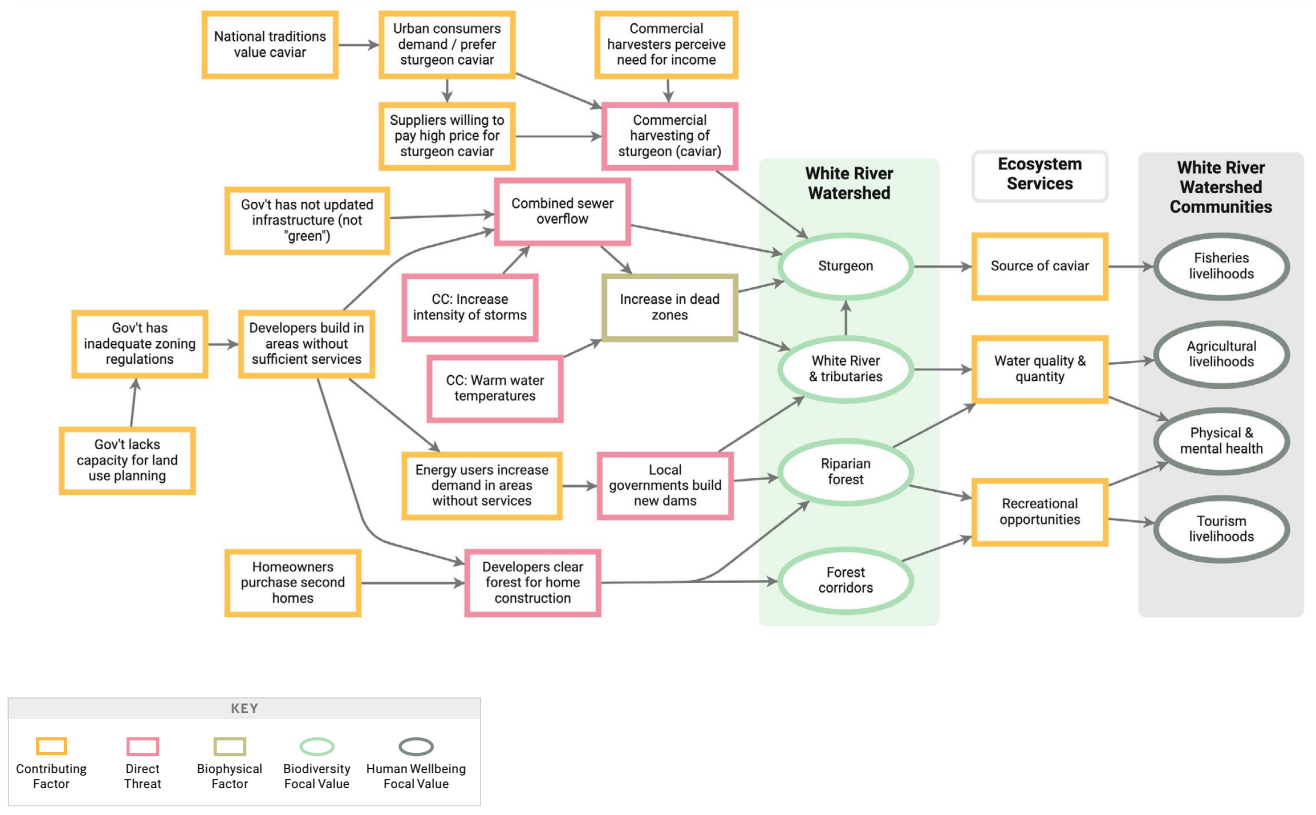

Situation Model

One way to synthesize and document threats, opportunities, and key actors identified in your situation analysis is to construct a situation model (also known as a conceptual model). A situation model is a diagram that visually portrays the relationships among the different factors in your situation analysia. See Figure 3 for a generic model and Figure 4 for an example based on a placebased project. A good model illustrates the main cause-and-effect relationships that exist within the project scope and the key actors involved. It should include the most important details, yet be as simple as possible. To this end, a situation model for a large scale project may need to be at a coarser grain than a model for a small scale project.

To make sure that your situation model generally represents your team’s understanding of your context, it is good to build it together and base it, as much as possible, on existing evidence and diverse knowledge systems. It may also be useful to develop a spatial map of your situation. For both your situation model and spatial map, it is ideal to review them with key actors, interested parties, and partners to make sure that the products reflect a shared understanding of the situation.

Figure 3:Generic situation model of project context.

Figure 4:Example situation model for a watershed site.

As you develop your situation model, take note of the evidence for linkages you are creating. That evidence may come from various sources (e.g., published literature, research data, traditional knowledge, expert opinion, or input from interested parties). Likewise, the evidence may differ in strength of inference, from certain to unknown. Do not merely focus on what you already understand. Laying out these relationships and their evidentiary support will help your team identify and prioritize actions, as well as discover weak points in your situation model and/or results chains (Step 2A).

If your team includes human wellbeing focal values in your situation model, you should show how key factors in your situation model affect those focal values, either directly or through the status of biodiversity focal values and associated ecosystem ervices . Figure 5 shows an example of how a threat to biodiversity may also threaten human health, as well as how the status of a focal value and its ecosystem services can affect human wellbeing.[5]

Figure 5:Example situation model extract with human wellbeing focal values.

1C OUTPUTS

- Identification and analysis of indirect threats and opportunities

- Assessment of interested parties and their primary interests

- Situation analysis and/or model, narrative description, and/or other representation of key cause-and-effect relationships among factors affecting your project context

ASSESS RESOURCES

CS Library Resources: Filter by “Assess” and then search within, if desired, by guidance, case studies, or other search terms

Recipes for Conservation: A Conservation Standards Toolkit: Navigate to the relevant Tipsheets in the Recipe Toolkit, as well as the Assess sections in the Examples & Resources document

Real-world Examples of Applications of the Conservation Standards

This figure provides an alternative way to show the relationship between your biodiversity focal values and human wellbeing focal values that may resonate with different audiences. See CMP (2016) Incorporating Social Aspects and Human Wellbeing in Biodiversity Conservation Projects for further guidance. Note this guidance will likely be updated over time.

In CS 5.0, we are substituting the term “focal value” for the previously used term “target.” This change is to be consistent with the Convention on Biological Diversity and other international fora which use “value” for the focal element of a protected area and “target” for the desired future measurement of a SMART goal or objective (e.g., the 30 x 30 target).

Ibid

The synonym “pressure” may be helpful in cases where the term “threat” may not be well received by interested parties (e.g., ranchers or loggers) whose actions or professions might be identified as a “threat.” It is also helpful to use adjectives such as “unsustainable” or “illegal” to clarify the nature of the threat (e.g., unsustainable ranching).