JPA Funding Strategies 💵

For long-term woody feedstock supply agreements in California

Abstract¶

This review analyzes funding strategies to secure sustainable funding for Joint Powers Authorities (JPAs). The California Governor’s Office for Land Use and Climate Innovation provided funding to develop multiple feedstock supply aggregation pilots throughout California. Proposed JPA entities acting as facilitators for long-term woody feedstock supply agreements could be a viable option. Sustainable funding for each JPA will be challenging, especially in rural areas without the tax base to support sales tax increases or similar local bond measures. Starting with traditional funding sources and complementing them with new funding strategies or dependable income sources will provide a more secure approach to long-term organizational stability. We include an in-depth analysis of the funding required to sustainably operate five pilot JPAs through an endowment investment, aiming to reduce state costs over time. Note that an endowment would not be limited to these examples. Recommendations include piloting new approaches, such as conservation finance, leveraging public funding with private sources, and utilizing the most suitable revenue source for the location and the entity being developed.

1.1JPA Funding Strategies¶

Joint Powers Authorities (JPAs) are proposed as a solution in California to facilitate agreements with forest landowners and managers, thereby creating long-term supply contracts and increasing investor support for wood products businesses. Funding JPAs presents challenges, given the difficulties of securing grants and private investments. Creating a diversified funding portfolio is crucial, especially for new entities, and suggestions for achieving this are provided.

What is a JPA?

JPAs are legal entities comprising local governments, such as counties, cities, and special districts, or combinations thereof. Alternatively, these government agencies can enter into contracts using these authorities as a limited tool to work within one another’s jurisdictions to accomplish regional project implementation. Identifying or creating such legal entities that could work with the biomass residue markets was a key component of the California Forest Residual Aggregation for Market Enhancement (CALFRAME) pilot, funded by the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation. This funding strategy for such JPA entities is adapted from this broader effort, with more detail available from Darlington & Stevenson (2023).

JPAs can help drive economic development by providing

Shared risk mitigation;

Improved service delivery, including contract development/management for third parties;

Cost-sharing, grant pursuit, and shared staffing;

Enhanced coordination among participating agencies, cities, and counties; and

Jointly established bonds, debt, and insurance tools, and public infrastructure finance Darlington, 2025.

1.1.1Takeaways¶

Developing diverse funding sources is always a sound strategy. Additionally, creating steady and dependable income sources can help complement the dynamic world of grant funding. Sources may include large tranches of funds to create endowments that in turn create a steady stream of income from interest or investments of the principal. Additional takeaways are the following:

Portfolio strategy. Be strategic about what funds you utilize for different projects and programs. Look to public funds, foundations,[1] and business support grants for organizational startup or administrative costs. Still, there are implementation grants for field projects and private or bank loans for scaling once a JPA is established.

Temporal ramping. Revenue sources outside the realm of taxes and grants may be difficult to create and execute with risk-averse agencies and organizations. Try funding with traditional resources, such as grants, first, and then gradually introduce new resources to diversify your funding portfolio and help establish the new organization’s financial stability over time.

Grant dependence & giving. In a similar vein, just because grants are available does not mean that will be the case indefinitely. As soon as you secure a grant, leverage it with other funding sources and work tirelessly to create more dependable and steady income sources. Remember that the single largest source of charitable giving in the United States comes from individuals, not foundations, corporations, or grant-making agencies. Individual contributions are also the least restricted type of funding, making them critical for covering operational expenses. Develop a strategy to cultivate local support through individual donations and campaigns.

1.1.2Background¶

The large wildfire seasons of the past five years were catastrophic for forests and communities. However, according to Keeley & Syphard (2021), these events are not unprecedented in recent California history and are typically associated with periods of drought, e.g., the 1920s and 2010s. According to North et al. (2022), tree densities in the Sierra Nevada have increased by up to sevenfold over the past century, while average tree size has decreased by 50%.

Not only does this overcrowding weaken forest health, but excessively dense forests also cause fires to burn more severely. A meta-analysis led by Hagmann et al. (2021) showed a fire deficit and widespread alteration of ecological structure and function across seasonally dry forests of western North America. A chronic level of stress is created by high competition across tree stands, resulting in reduced resilience to drought, disease, fire, and climate change. North et al. (2009) advocates for an aggressive approach to treating fire-suppressed stands using an ecologically-based approach that reduces the total number of trees/acre while maintaining stand heterogeneity.

1.1.3Feedstock Aggregation¶

Thinned forests create a lot of biomass, and much of that biomass from forest health projects ends up in burn piles or log decks and may stay in these locations indefinitely. Not only does this negate fire mitigation efforts, as burn piles and decks can promote or worsen fires, but the carbon from wood is also at risk of not being sequestered.

Processing biomass from thinning is challenging; Swezy et al. (2021) found that the cost of forest restoration far exceeds current market prices for biomass. Becker et al. (2011) point out that supply guarantees, industry presence, transportation, and the value of the biomass are limiting factors to utilization, whereas agency staffing, budgets, compliance, and partnership aggravated utilization problems rather than impeding progress. A burn pile inventory across California showed massive wood tonnages scattered through national forests and other lands Darlington et al., 2023. Yet burning those piles is likely more expensive than transporting them to a facility for processing (Barker et al 2024).

Transportation subsidies to move this feedstock to central locations or nearby facilities, as well as establishing right-sized facilities in areas with sufficient feedstock, could be a crucial missing component in addressing the wildfire problem across the western United States.[2] Transporting the feedstock to a central location, accessible and central to processors, biomass facilities, and wood product businesses, would help move the biomass out of the woods, mitigating fire risk while also facilitating the centralization of long-term feedstock contracts with landowners and managing agencies.

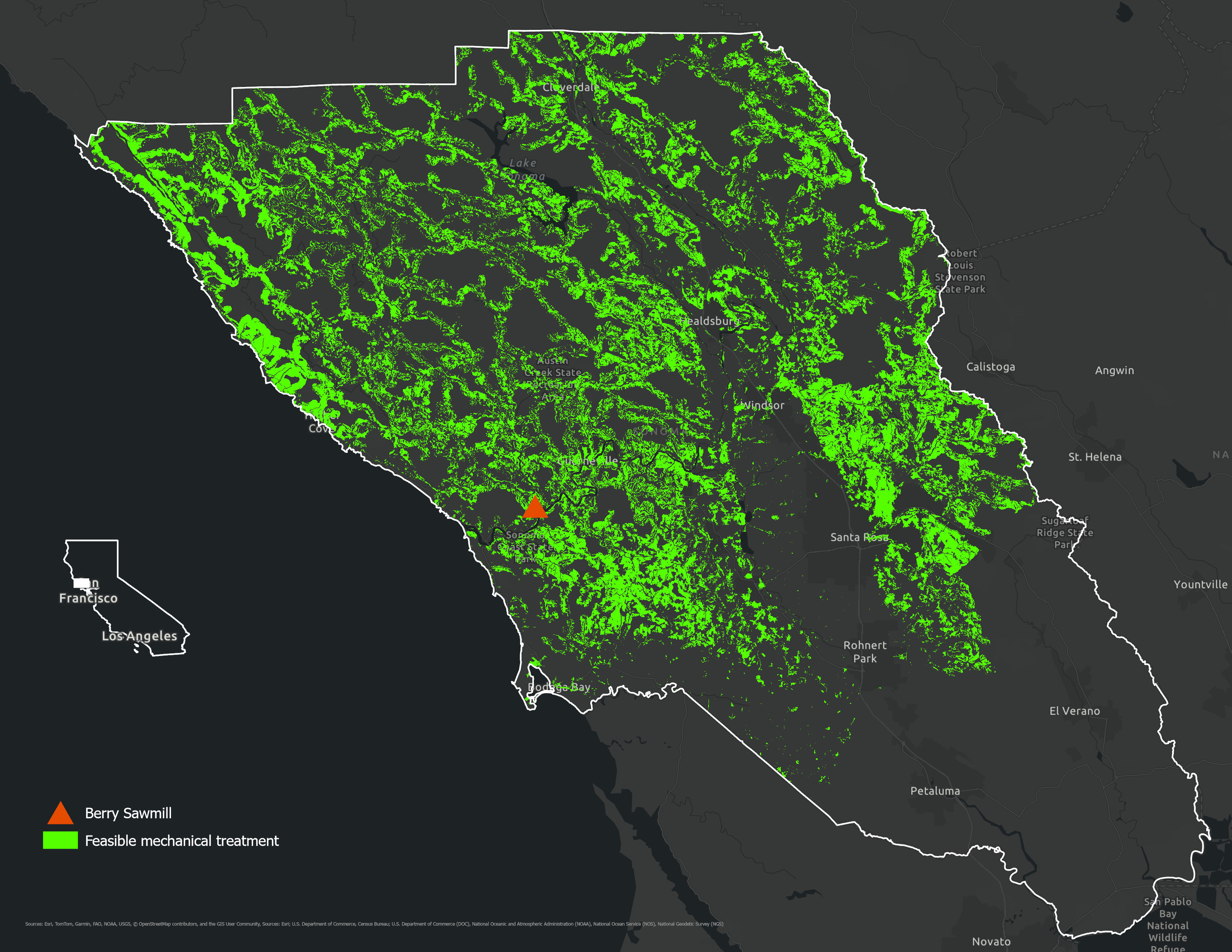

For instance, Regenerative Forest Solutions identified approximately half (242,365 acres) of Sonoma County’s forested acres as feasible for treatments (Figure 1.1). Creation of a coordinating entity and establishment of a wood campus at an existing, permitted sawmill site, Berry’s Sawmill in Cazadero, California, were identified as effective strategies for increasing the utilization of forest biomass residuals Costa, 2025. Creating similar entities and wood campuses across the West could make it easier for investors to de-risk investments. Joint Powers Authorities may be an organizational template that can meet these needs. Swezy & Oldson (2025) cautioned against starting new sort yards in northeast California, instead focusing on supporting existing biomass facilities, offering insurance to existing wood yards, and securing funding for a consistent pipeline of environmentally compliant (CEQA/NEPA) projects on which operators can bid.

However, an overarching limitation to utilizing forest biomass is the inability to commercialize small-diameter wood, slash, or other wood waste. A vast amount of biomass in this category is outside of Timber Harvest Plans (THPs) and Nonindustrial Timber Management Plans (NTMPs). Utilizing this wood could reduce high-grading, offsetting the costs of timber management and opening opportunities for community-based wood products. Delyser et al. (2025) found that 39-50% of forest treatment costs could be offset through the recovery and utilization of non-commercial wood as the highest and best use of this material and an important contributor to Climate Smart Forestry see Nabuurs et al., 2018. It is possible that JPAs could also help facilitate increased utilization of wood products, working with CAL FIRE to examine pathways to increase utilization across all organizations and communities.

Figure 1.1:Feasible treatment areas of Sonoma County and the location of Berry’s Sawmill as a feedstock aggregation and processing site—adapted from Tukman & Griffith (2022). The green treatment areas exclude waterways, slopes above 45%, and biomass that is not within sufficient proximity to existing roadways.

1.1.4JPAs & Feedstock Aggregation¶

Developing JPAs as a management entity for feedstock aggregation is a key component of the California Forest Residual Aggregation for Market Enhancement (CALFRAME) pilot, funded by the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation. This funding strategy for a JPA is adapted from this broader effort, with more details available from Darlington & Stevenson (2023).

Perhaps the most critical challenge to biomass utilization is establishing long-term feedstock supply contracts. For example, the USDA Forest Service, which manages 60% of California’s forests, typically allows a maximum of five years for a feedstock supply contract CSG, 2020.

JPAs could act to facilitate long-term contracts between suppliers and processors, thereby driving investment in processing facilities.

The lack of long-term contracts makes investment in wood utilization businesses risky. Creating new JPAs in some regions may be a solution to address this issue. JPAs could act to facilitate long-term contracts between suppliers and processors, thereby driving investment in processing facilities. Most lenders and investors view wood product businesses as too risky without a minimum term contract of 10 years, preferably longer Darlington & Stevenson, 2023. The USDA Timber Production Expansion Guaranteed Loan Program (TPEP) was established for this reason and is a potential funding source for facilities.

JPAs are now poised to utilize residues from local and regional forest health and wildfire reduction projects. They work with community partners and collaboratives to avoid duplicating efforts or mitigating unexpected competition between local partners. JPA proponents recognize that funding for this effort will be challenging, given the wide fluctuations in private and public funding. Developing sustainable revenue sources may be especially challenging for rural counties with low tax bases that cannot support a sales tax to establish the JPA and provide stable revenue for the entity to operate.

Creating stably funded JPAs will be challenging given the wide fluctuations in private and public funding.

The establishment of JPAs as biomass facilitators is at differing stages across the state. During the establishment or modification of existing JPAs, participants have been clear about the entity’s role: to act as a critical entity for long-term feedstock supply contracts without competing for funds with other organizations, such as Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs), sawmills, or licensed timber operators (LTOs). This approach requires a realistic revenue assessment and a plan for the initial five years of operation, acknowledging that creating stably funded JPAs will be challenging given the wide fluctuations in private and public funding. This may be especially challenging for rural counties with low tax bases that cannot support a sales tax to establish the JPA and provide stable revenue for the entity to operate.[3]

LTO and RCD role in forest management

Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs) are quasi-governmental, non-regulatory agencies, typically special districts with limited powers, based in California’s counties, that provide critical resources, funding, and training to address forest health. There are approximately 40 RCDs with forestry programs that focus on implementing thinning, prescribed fire, and providing technical assistance to private landowners, as well as collaborating with other organizations (CARCD).

Licensed Timber Operators (LTOs) are the loggers licensed to operate forestry operations in the state of California. They are licensed under the state’s Forest Practice Act Law and authorized to conduct tree cutting and removal (CAL FIRE). During the past decade, LTOs have been critical to carrying out forest health projects funded by CAL FIRE and others to reduce wildfire risk and improve forest resilience. Their limited numbers have at times curtailed forest health projects.

1.2Funding Options¶

The abundance of state and federal funding over the past five years has led many agencies and organizations to rely heavily on grant funding for implementing restoration and infrastructure projects. The Trump administration’s cuts in 2025, combined with California’s periodic surpluses and deficits in state funding, demonstrate the vulnerability of grant funding dependence. Many organizations are familiar with the cyclical nature of funding sources and seek to create more dependable, even-keeled funding streams, although grants can often complement stable revenue streams.

1.2.1Traditional¶

Many of the Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation’s CALFRAME feedstock aggregation pilots recognized the need for long-term funding sources and that grants are not a dependable resource to maintain an organization over time. Traditional funding sources are many, and a blended portfolio should help weather changes in grant cycles and tap into funding sources that can provide steady revenue. These options are described below, with the pluses and minuses of each summarized in (Table 1.1). Other revenue sources, such as climate bond funding, agency funding, and legislative action, are also available, but their outcomes tend to be grant-based and temporary.

Endowment. In the case of the feedstock aggregation pilots, the Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation provided a funding tranche to kickstart JPA creation. This funding could potentially be used to create an endowment or, at the very least, seed an endowment that could provide a steady source of unrestricted revenue if invested wisely. Other JPAs could do the same with an initial foundation grant or a campaign, such as a bond measure, to raise sufficient funds to start an endowment.

Contributions. A capital campaign to raise awareness about a JPA and generate individual, corporate, and foundation grants would complement any secured funds. Match from non-public sources often makes grant applications more competitive. A well-defined JPA strategy that clearly outlines the mission, programs, and projects is crucial for focusing funding requests. Similarly, for any grant application, it prioritizes which funding to pursue Russell et al., 2024. Capital or general campaigns can be an excellent vehicle to drive individual donations and raise awareness about the importance of the issue at hand.

Federal and State Grants. JPAs should be competitive for a variety of state and federal grants and be able to budget overhead costs (~10%) and directly bill salaries to cover a portion of operating costs. A negotiated indirect cost rate agreement, or NICRA, to increase indirect limits through public grants could be another approach to boost operating cost revenues.

Member Contributions. JPA members or beneficiaries, such as RCDs, pay an annual cost to participate in the feedstock aggregation program. Membership would provide consistent revenue and encourage the member organizations to be involved in the development and success of the JPA.

Fee-for-service. Charging fees for forest management, timber harvest plans, feedstock contracts, or grant administration, depending on the skills of the JPA staff, could be another way to generate a steady income source. Western Shasta RCD, for example, works with non-industrial forest owners to develop forest management plans. The State can fund the development of forest management plans for private landowners. A JPA could offer similar services as long as it does not compete with RCDs in the region.

Sort yards. Managing a sort yard for aggregated feedstock could be a strategic revenue source, but some regions found a lack of feasible revenue for sort yards.[4] Note that feedstock aggregation and sort yards should not be conflated, nor should the creation of JPAs be thought of as sort yard managers. A sort yard may be one strategy for income generation, but it is not necessarily connected to the goal of a feedstock aggregation JPA, which is to facilitate long-term supply contracts.

Table 1.1:Analysis of funding types suitable for aggregation JPAs. Timing roughly refers to the amount of time required to generate income. Difficulty is a qualitative scale ranging from 1 (easiest to secure) to 5 (most difficult). Note that sort yards are not to be conflated with JPA creation or feedstock aggregation.

Type | Pluses | Minuses | Timing | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Endowment | Steady income from principal | Need significant amounts to generate income | May take a long time to build principal | 5 |

Individual Contributions | Unrestricted funding | Much time to manage individual contributions | Instant | 1 |

Public Grants | Access to large amounts of money | Reimbursable, administration costs can be high, stiff competition, and cyclic | Public grants may take a long time from proposal to contract execution | 2 |

Private Grants | Often include unrestricted funding | Dependent on relationships with program officers, board members | Lengthy time for relationship building | 3 |

Fee-for-Service | Steady income based on capacity and experience for services | Staffing, unevenness of demand | Long time to develop and market services | 3 |

Sort Yard | Steady income, demand for wood is high | Transportation costs, management, long-term supply | Permitting and capacity building take time. | 4 |

1.2.2Endowment Analysis¶

Endowment-based funding represents a promising and underutilized strategy for ensuring the long-term financial sustainability of JPAs engaged in forest health and feedstock aggregation. Unlike grant-dependent models, which are vulnerable to the cyclical nature of public budgets and shifting political priorities, endowments can provide a stable and predictable revenue stream. Endowments may be the most strategic way to fund JPAs, especially since some may struggle to secure grant funding in the future, given their long-term focus on feedstock supply contracts.

How it Works¶

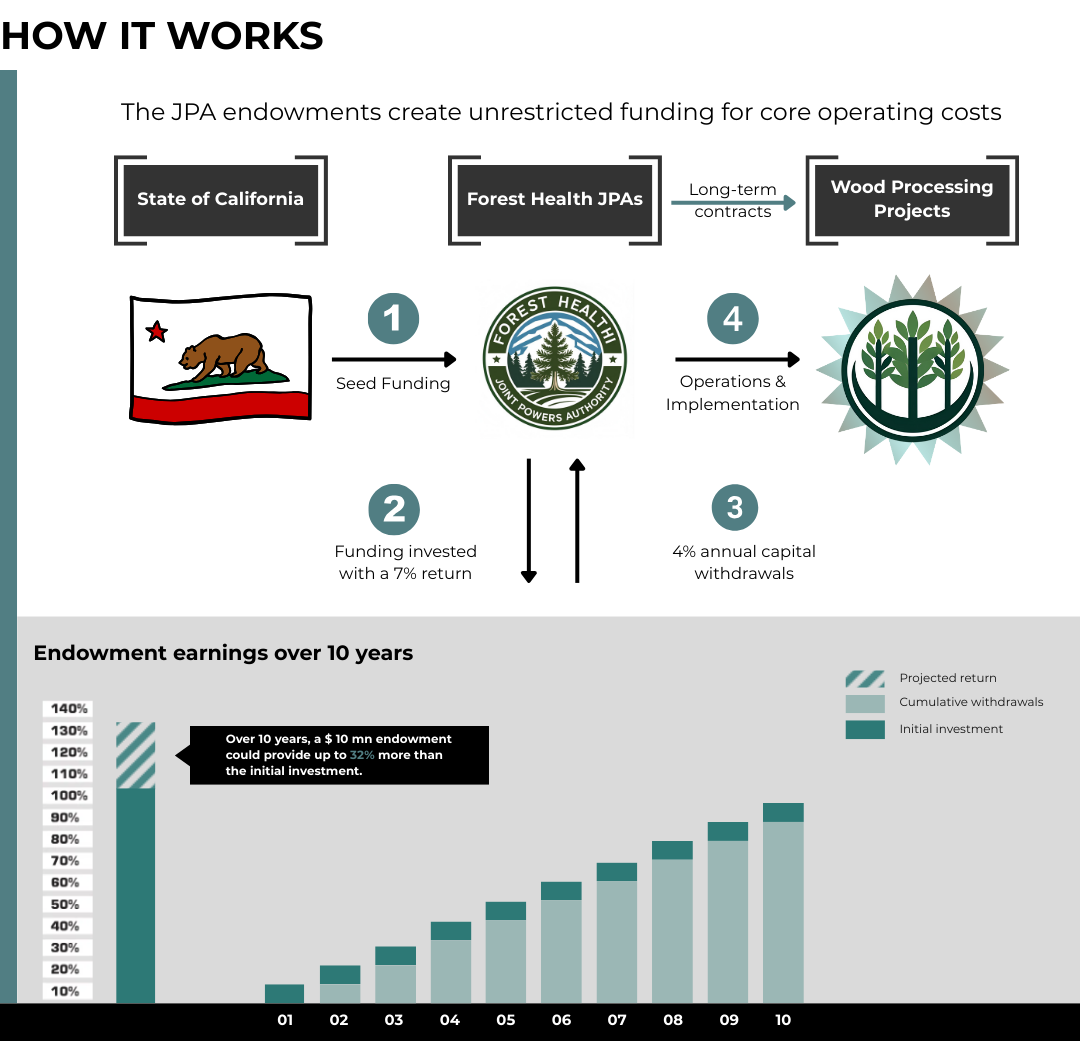

By investing a substantial principal—such as an initial gift of $10 million—and supplementing it with modest annual contributions, a JPA can generate consistent income to support core operations, staffing, and potentially even programmatic expansion (Figure 1.2). The administrative burden and ongoing costs associated with managing an endowment are typically lower than those required for continuous grant writing and reporting, making this approach attractive for organizations seeking to minimize overhead.

Figure 1.2:Endowment operations and potential earnings over 10 years with a 7% return, 4% annual spending rate, and 0.2% administrative fees. The total return over 10 years is estimated to be 32%. Withdrawals would be from interest earned from the principal. Returns may be lower or higher than 6% so the investment may increase or decrease more or less than the linear increase indicated in the chart. Graphic adapted from Synchronicity Earth (2025).

Financial calculations illustrate the impact of the initial investment over time, compared to annual grants or allocations. With a conservative yearly return of 7%, a spending rate of 4%, and an administrative fee of 0.2%, an endowment of $10 million could yield approximately $400,000 in its first year, with annual income rising to nearly $448,000 by year 5 (Table 1.2). This steady growth not only insulates a JPA from the volatility of state surpluses and deficits but also frames endowment funding as a long-term cost-avoidance strategy for public agencies and private donors alike. By establishing a robust endowment, JPAs can ensure operational continuity, attract and retain skilled staff, and maintain the flexibility needed to respond to emerging challenges in forest management and wildfire mitigation.

To calculate the required endowments, we estimated 5-year returns with a 4% annual spending and a modest 7% annual return. A 0.2% administrative fee and an additional $5,000/yr in individual contributions were factored into the return calculations. We set each endowment to the closest $100,000 that created a 5-year return exceeding the estimated 5-year budget created by each pilot team.

Table 1.2:Example endowments ($USD) based on five pilot JPA annual budget estimates. The 5-year budget is an estimate from the respective JPA proponents. Average returns are based on a 7% return with income generated averaged over the 1st five years. An estimated 0.2% administrative fee and $5,000 contribution to the principal are included in the calculations. The Central Sierra South example is being developed from an existing JPA (Central Sierra Economic Development District or CSEDD) and, therefore, may not be directly comparable to the other four startup JPAs. A similar example in development is the Eastern Sierra Council of Governments (ESCOG). RRA = Risk Reduction Authority, FBA = Forest Biomass Authority, RFS = Regenerative Forest Solutions. JPA endowments are not limited to these examples.

| JPA | 5-yr Budget | Endowment | Avg. Return | 5-yr Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Sierra Tahoe | 1,293,750 | 6,470,000 | 258,733 | 1,293,663 |

| Central Sierra South | 1,386,080 | 6,930,000 | 277,222 | 1,474,272 |

| Lake County RRA | 1,380,662 | 6,900,000 | 276,132 | 1,469,175 |

| Northeast CA FBA | 2,067,375 | 10,340,000 | 413,475 | 2,067,375 |

| Sonoma County RFS | 2,809,895 | 14,050,000 | 561,979 | 2,809,895 |

| TOTAL | 8,938,762 | 44,690,000 | n/a | 8,940,719 |

Avoided Cost Estimate¶

Let’s assume that it would cost $115,000/yr for a state agency to manage a grants program.[5] This includes staff, administrative, and operating costs. If we add an annual rate of inflation of 4%, that gives a total five-year cost of $622,877 for grant administration. The five-year budgets from the JPAs would likely form the basis of grant requests; therefore, the grant administration plus five-year budgets totals $9,561,639.

Although the granting agency return on investment is really the public benefit from making the grants for project implementation, these operating costs would provide an ROI of -100% since there would be no return (Table 1.3). That ROI would continue to decrease over time, e.g., become more costly for the State, as the program continues to support the JPAs via grants.

On the other hand, the initial investment of $44.6 million for the endowments amortizes to ~$8.94 million over five years and gives a return of nearly $9.2 million or 21%. The return for the endowments would continue to grow and not be a recurring state cost, allowing state funds to be invested in other JPAs or new projects.

Table 1.3:Avoided 5-year costs ($USD) estimated from the five pilot budgets vs. estimated agency costs to manage grant funds. The return is a 5-year return. ROI = Return on Investment.

| Program | Investment | Return | ROI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endowments | 8,938,762 | 8,940,719 | 21 |

| Grants | 9,615,071 | -9,615,071 | -100 |

Revolving Loan Fund¶

An innovative approach to multiplying the impact of a JPA’s funding endowment is to allocate a portion of the principal for low-interest loans to forest health operations and wood products businesses.[6] By acting as a community-based lender, the JPA can support local projects that might otherwise struggle to access affordable capital, accelerating restoration and market development. The interest payments received from these loans can then be reinvested into the endowment, steadily growing the principal over time. This strategy not only amplifies the reach of the original endowment but also creates a self-reinforcing cycle of investment and impact, enhancing both financial sustainability and landscape resilience.

Maryland’s Revolving Loan Fund Success

Maryland’s Shore Erosion Control Revolving Loan Fund, created in 1964, provides 0% interest loans to landowners to utilize natural solutions for shoreline erosion control Crook, 2021. The fund was initially capitalized with $1.5 million, with an additional /$650,000 added in the 1970s. Since then, it provides 15-20 loans annually up to $700,000 with 15% of repayments to cover administrative costs and 85% returned to the fund. As of 2021, the fund provided more than 700 loans over 52 years.

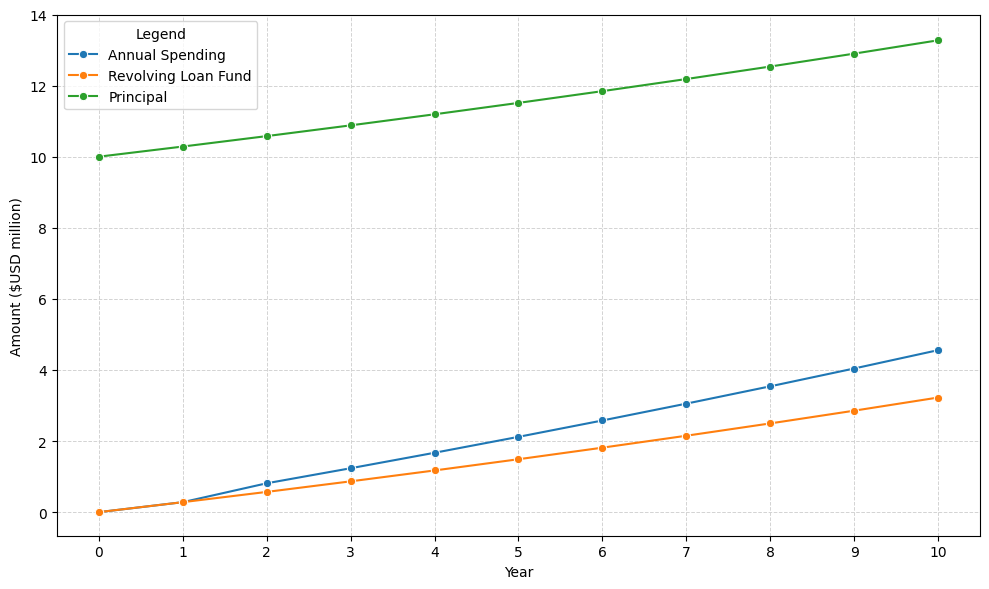

The economics of a revolving loan fund depend on several key factors: the total annual return from the principal, the yearly amount loaned out, the interest rate charged, and the loan performance period. The calculated returns in Table 1.2 are based on a modest 7% return with a 4% spending rate. If the JPA governing board added guardrails to revolving loan spending, interest rates, and other factors, presumably 1-2% of the return could be set aside for a loan fund that is carefully loaned to local organizations when a predetermined amount is reached. If the loan interest rate is a point or two above the endowment earning rate, then that would allow the revolving loan principal to grow. There’s a risk of unpaid loans, loans that take too long to repay, or excessive loan amounts, but these factors could all be mitigated through the JPA’s bylaws.

Over 10 years, a $10,000,000 endowment with a 7% annual return, 4% annual spending, a 0.2% administrative fee, and $5,000 added each year would generate a steadily growing cumulative loan pool. By setting aside the yearly earnings above the spending and administrative costs, the loan pool would reach approximately $3.2 million by year ten (Figure 1.3). This approach allows the JPA to support additional projects through low-interest loans while maintaining the long-term growth and stability of the endowment.

Figure 1.3:Hypothetical creation of a revolving loan fund from a $10 million endowment with 3% set aside annually, 4% spending for operating costs, $5,000 annual contribution, and 0.2% administrative fee.

Forest Resilience Authorities¶

Another model could be a special fund established in statute at the state treasury and capitalized with a $250 million endowment, with LCI designated as the administrator. There are clear advantages and trade-offs to managing the fund as a single pool versus distributing one-time endowments to each aggregation pilot. Centralized management by a state agency could streamline administration, reduce overhead costs for individual pilots, and provide each entity with access to a larger, more diversified pool of funds. This approach would also ensure consistent oversight and potentially greater investment returns due to the scale of the endowment, while guaranteeing each pilot entity an annual appropriation to finance its operating budget. Higher returns may be possible with the larger pooled funds.

New vs. Existing JPAs

Endowments for feedstock aggregation pilots are not limited to the examples given and may be created from new or existing JPAs.

For example, the Eastern Sierra Council of Governments (ESCOG) is comparable to CSEDD, where proponents are adding feedstock aggregation functionality to an existing JPA and also forming a local collaborative connected to forest health and fuel treatments for wildfire mitigation. Where strong JPAs exist and there is interest in creating a special district, this may be the best route to follow, given that JPAs take a long time to form. ESCOG, for instance, took six years to create.

Creation from existing authorities may also make startup and implementation much less costly over time.

However, managing the fund as one large sum may limit the flexibility of each pilot entity to respond to local needs, as access to additional funds for loans or grants would be subject to a competitive process administered by LCI. In this model, each pilot would be designated as a Forest Resilience Authority under state statute and guaranteed an annual appropriation through the fund to finance its operating budget. While this could foster innovation and ensure that funds are allocated to the most impactful projects, it may also introduce uncertainty for authorities that rely on supplemental funding for infrastructure or project development. In contrast, issuing one-time endowments directly to each pilot entity would empower them to make independent decisions about granting or lending funds, tailoring their financial strategies to the unique needs of their service areas.

Under the centralized model, with a 5% interest rate on $250 million, approximately $12.5 million in earnings would be generated in the first year. If 90% of these earnings are distributed as grants and 10% reinvested/used for administration, about $11.25 million would be available annually to support pilot operating budgets and project funding. This structure would provide pilots with a stable base of support while leaving a substantial pool—over $9.5 million in year one—for competitive grants or loans to finance infrastructure, transportation subsidies, and other critical needs, with the potential for these resources to grow and fund new or existing JPAs as feedstock aggregation entities as the endowment appreciates over time.

Grant Leverage¶

Although we don’t have evidence to support this theory, we suspect organizations with a solid endowment will be more competitive for public funding, given their ability to provide a match and solid operating revenue. Established endowments offer a source of unrestricted funds that can be strategically used to meet grant match requirements for state and federal funding opportunities. With a robust endowment, organizations can offer greater match amounts, making their grant applications more competitive and attractive to funders. Additionally, a solid core operating budget supported by endowment income ensures organizational stability and the capacity to manage and implement grant-funded projects effectively.

1.2.3Temporal Adoption¶

Any funding strategies, whether they are traditional or new conservation finance approaches, may be new or untested for certain audiences. Raising funds from conventional resources and then piloting new options over time may be the best approach to introduce novel income sources. For example:

New finance options, such as environmental impact bonds, could be introduced over a longer period and trialed at a small scale, then scaled up when successful. These could also include other financial mechanisms, such as revolving loan funds (offering low-interest loans), public-private partnerships, or bonds.

Other revenue-generating options could be tested in the same manner to ensure their effectiveness and introduce them to skeptical participants, financial managers, or government entities that are not used to working with alternative finance options.

1.2.4Collaborative Finance¶

Collaborative finance is a conservation finance strategy that involves cooperative interaction between individual project developers, stakeholders, and finance providers Russell & Odefey, 2024. This process may or may not include traditional financial institutions.[7] The term can be broadened to include finance developed through the fair and equitable participation of stakeholders in a region, landscape, or watershed, addressing natural resource and infrastructure management needs, and utilizing multiple forms of funding, from public grants to private investment. Finance approaches may include outcomes-based finance models such as environmental impact bonds.

The challenge of new finance options vs. more traditional approaches is, simply put, they’re new. As a result, more conservative controllers, accountants, and similar financial managers within any organization will be resistant to implementing new, unproven methods for generating income. Consequently, it may be best to start strong with traditional approaches and gradually test new strategies. Feasibility studies may also help introduce collaborative finance and new approaches. However, there are examples of established and successful impact finance bonds on the North Yuba River to draw upon when creating novel funding streams.

New Funding Options

New Finance Options Conservation finance options include environmental impact bonds, such as Blue Forest’s Forest Resilience Bonds, which leverage private investment from impact investors to support forest health projects. Repayment to investors is supported over time by beneficiaries, such as water districts, based on the savings and benefits from reduced wildfire risks and improved ecosystem services. A JPA could utilize environmental impact bonds on a trial basis at a small scale and then expand over an extended period. Identifying potential payor entities interested in covering the avoided costs of wildfire through proactive measures, such as thinning and prescribed fire, is worth pursuing immediately or as soon as an executive director is hired.

We do not recommend relying solely on impact bonds, as they take a lengthy time to develop and rely on a payor to provide avoided cost funding. However, a bond could be a valuable complementary funding resource to other secured revenues. Other ‘newer’ finance options could include the following:

Carbon Markets Carbon markets offer an opportunity to secure funding for on-the-ground forest management activities, including thinning, pruning, mastication, mechanical treatment, and prescribed burning. Revenue realized through carbon markets could help a JPA to treat more forest land than otherwise possible and generate additional biomass that could be put under supply contracts. Market prices for carbon credits vary depending on a given project’s size, location, treatment type, and the specific carbon market or registry used. Carbon credits can be generated for projects of any size, regardless of their location on federal, state, or private lands. Refer to the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol section below for an alternative approach that is easier to implement than carbon sequestration credits or markets, as the avoided costs are already calculated, and proponents do not need to seek an entity to purchase the credits.

The National Forest Foundation implemented several voluntary carbon projects in California and the West following wildfires. Funded by corporate donors, the projects created carbon credits based on the growth trajectories of planted trees. The credits were registered with the American Carbon Registry but were immediately retired upon creation, as trading carbon on public lands is prohibited.

Avoided Wildfire Emissions The Spatial Informatics Group and Element Markets developed a forecast methodology under the Climate Forward program to recognize the climate benefits associated with fuel treatment activities that reduce the risk of catastrophic forest fires and their associated emissions. Known as the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Forecast Methodology, the protocol could provide complementary funding for thinning and prescribed fire projects, in addition to grants and private investments. The Protocol differs from carbon offsets in that forecasted mitigation units (FMUs) are issued for forecasted reductions or removals of greenhouse gases. FMUs are used to mitigate anticipated future emissions, such as wildfires. This methodology, however, uses outdated allometric equations to calculate changes to forests and does not model fire or climate. Verra’s Methodology for Avoided Forest Conversion from Decreased Wildfire may be a more accurate approach to tracking treatment impacts on carbon stocks over time.

Embodied Carbon Although it may be several years from implementation, developing and marketing low-carbon building materials is another new opportunity. Buildings are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, making building decarbonization a California state priority. Embodied carbon is the lifecycle of greenhouse gas emissions from creating, transporting, and disposing of building materials (Carbon Leadership Forum, 2022). In other words, embodied carbon is any building’s carbon footprint contained in its building materials. It differs from operational carbon, the carbon produced by a building’s energy, heat, and lighting. The California Air Resources Board is developing a comprehensive strategy for embodied carbon and is seeking comments following the signing of ABs 2446 and 43.

Revolving Loan Funds Pooled funding sources, such as impact bonds or revolving loan funds, can help make a greater amount of funds available to more projects across a landscape. Typically offered at below-market interest rates, revolving loan funds are self-replenishing pools of money that utilize principal and interest payments on existing loans to issue new loans. They have been used effectively on both small and large scales to develop businesses, support healthcare, and improve environmental outcomes. Revolving loan funds also provide much-needed upfront capital for project startups. They are flexible and can be used in conjunction with more conventional funds, such as grants and loans.

For example, through a coalition of public and private partners, the Southwest Wildfire Impact Fund aims to utilize resources from private investors and revenues generated from biomass produced through forest thinning to offset the financial burden of wildfire mitigation in the San Juan National Forest’s wildland-urban interface. The project fosters regional collaboration through shared project financing and implementation. It also creates the opportunity for scaling up forest treatments and fire reduction by creating a revolving loan fund that reinvests proceeds into additional projects, ensuring that capital is available for long-term re-treatment and expansion of forest health interventions.

Blue Forest is operating a revolving loan fund called the California Wildfire Innovation Fund, which could expand into broader support for other forest health entities.

Parametric Insurance Parametric or index-based insurance covers the probability of a predefined event, rather than indemnifying the actual loss incurred Re, 2023. These so-called trigger events are typically disaster-related (e.g., wildfires, flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes). They are measured through triggers such as wind speed, earthquake magnitude, acres burned, burn severity, or rainfall amount. Insurable triggers are modeled and must happen by chance. When the triggers are reached, a predetermined payout is made regardless of the sustained physical losses. Parametric insurance is meant to complement existing indemnity insurance but is increasingly used for post-disaster restoration funding in the natural world.

One of the earliest examples of parametric insurance used for nature recovery is the Mesoamerican Reef parametric insurance that provided $800,000 for reef restoration following Hurricane Delta. The trigger was windspeed with a parameter greater than 100 knots. The funds originated from the Coastal Zone Management Trust. Utilizing insurance to protect forests and communities, likely through wildfire risk mitigation, could be a novel approach to funding activities throughout the region and provide complementary funds that could be particularly valuable post-fire.

Tech-based Solutions The technology could help connect funders to a new JPA. Blockchain and digital solutions have mostly been applied to reforestation and carbon sequestration projects. It may be possible to establish a digital marketplace where funders and implementers can connect and collaborate on implementing forest health restoration and infrastructure projects. Developing a platform for aggregated funding could be part of a funded project or developed in tandem rather than as a standalone initiative.

1.3Budget¶

Rough estimates for JPA creation in California for 2025 range from a bare bones budget of approximately $400,000/year to a more “inflation-proof” budget of $2-3 million/year for startup and sustainable implementation over time.[3]

1.3.1Revenue¶

Revenue may come from a variety of sources, such as grants, donations, and fee-for-service consulting. Contributions and gifts may come from local to regional foundations and corporations interested in forest health. Individual contributions always have the potential to add up to more than foundation and corporate gifts, as they are the largest charitable giving category in the United States. However, they require more time to manage. Creating a time-bound campaign with a specific fundraising goal replete with a thermometer to track progress could be a great way to involve communities in a region through giving and engaging them in the need for a JPA to ultimately mitigate wildfire threats.

In the case of pilot projects supported by the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation, a tranche of endowment-like funding is recommended for startup funding of aggregation entities. In some cases, this amount is as much as $1 million, which, along with a capital campaign to bolster individual giving and create awareness around a JPA, could create a base endowment and provide stable operational revenue to a new organization from the principal if the endowment funds are wisely invested.

Although not competing for grants with RCDs, a JPA may help administer a large grant across multiple RCDs to leverage more funds across a region. With the devolution of some state funding sources, this could be a great option for managing regional funds and reducing competition for funding resources, as the grants are allocated to local organizations.

JPA - RCD competition

Evaluating whether to form a new governmental entity or organization is an important consideration for feedstock aggregation. Working with existing organizations, such as Resource Conservation Districts or Fire Safe Councils, would be a good starting point. It is critical to incorporate into the JPA’s bylaws and revenue-generating practices that grant fundraising does not compete with RCDs. It is possible that a JPA may collaborate on a grant with one or more RCDs, but should never submit grants for which an RCD is eligible.

Contingency funding should be written into the budget expenses. Adding 10-15% contingency line items to any secured grant would supplement that funding; however, most grant funding contingencies are typically applied to budget shortfalls. Other contingency funding sources could include unrestricted funding (such as contributions or gifts) and a higher indirect rate.

1.3.2Expenses¶

An annual expense budget of ~$400,000-2 million is estimated for a JPA startup. The total expenses/year could slowly ramp up each year of the budget, with the idea that additional secured revenue would enable a JPA to bring on more staff capacity, increase offerings, reach, or fee-for-service activities, or undertake additional revenue generation activities. The bulk of the expenses is for labor and staff, although some JPAs operate completely through contracted staff.

Other expenses may include operations and maintenance, audit and legal fees, LAFCO filing, bylaw creation, insurance, equipment, software, travel, bank fees, communications, website development, outreach, and other related expenses.

1.4Recommendations¶

Funding JPAs is not a simple task, as most public funding sources are focused on project implementation, e.g., funding restoration projects in the field, rather than providing administrative support or organizational startup. Some foundations fund this type of work, but accessing those funds can be challenging. Another challenge is competing with existing entities for scarce local, regional, and federal resources. The following are recommendations to consider when examining the feasibility of building and maintaining a JPA for long-term feedstock agreements:

Utilize public funds for startup and traditional projects. Public funding is readily available and generally suitable for trials or the initial development of feasible but new ideas.

Pilot non-traditional, higher risk, or new revenue sources. Then, ramp them up with success, and participating entities and partners see their value and understand how they work.

Co-house staff and resources. Utilize existing offices and share staff and other resources as capacity and funding allow. This is particularly important during the startup and early phases of developing a JPA.

Leverage public funds with private investment. When public funds are secured, immediately work to leverage them with other public and private funding resources. Don’t wait until near the end of the grant cycle to look for additional funds.

Use the right revenue source. Property and sales tax increases are more effective in populated areas with higher incomes; however, they are usually not appropriate for rural areas, where the tax base and population tend to be too low to provide sufficient funding.

1.5Credits¶

A special thank you to Michael Maguire, LCI; Sharmie Stevenson, Fall River RCD; Joshua Harrison, Center for the Study of the Force Majeure; Temra Costa, Regenerative Forest Solutions; and Christiana Darlington, CLERE, Inc., for reviewing the draft manuscript. Thank you to the entire Northeast California CAL FRAME team for ideas, edits, and development of the CAL FRAME Entity Action Report to LCI. Eternal gratitude to Jeff Odefey, One Water Econ, for his collaboration in developing the initial ideas for this manuscript.

JPAs can receive funding directed to tax-exempt organizations without being a nonprofit. However, any tax benefits would be lost. It may be necessary to connect any funding, e.g., from a foundation, to a nonprofit fiscal sponsor.

The rule of thumb is a maximum 50-mile deadhead (empty trailer returning after dropping off payload) trip for timber or other forest products.

Sharmie Stevenson, Fall River RCD, personal communication.

Based on estimated cost to run a California state agency grant program per year. Michael Maguire, LCI, personal communication.

Revolving loan funds are a proven vehicle to fund grant programs, community development, and wildfire mitigation and have been in use worldwide for decades.

See collaborative finance for more information.

- Darlington, C., & Stevenson, C. (2023). Joint Powers Authorities: A tool to manage forest biomass residuals in California. CLERE, Inc. https://bof.fire.ca.gov/media/sbvcxfiy/cal-frame-jpa-noreast-opr-pilot_final-may122023.pdf

- Darlington, C. (2025). Local agency forest biomass market enhancement strategies and action July 10 presentation to Joint Institute for Wood Products Innovation AC Meeting.

- Keeley, J. E., & Syphard, A. D. (2021). Large California wildfires: 2020 fires in historical context. Fire Ecology, 17(1). 10.1186/s42408-021-00110-7

- North, M. P., Tompkins, R. E., Bernal, A. A., Collins, B. M., Stephens, S. L., & York, R. A. (2022). Operational resilience in western US frequent-fire forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 507, 120004. 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.120004

- Hagmann, R. K., Hessburg, P. F., Prichard, S. J., Povak, N. A., Brown, P. M., Fulé, P. Z., Keane, R. E., Knapp, E. E., Lydersen, J. M., Metlen, K. L., Reilly, M. J., Sánchez Meador, A. J., Stephens, S. L., Stevens, J. T., Taylor, A. H., Yocom, L. L., Battaglia, M. A., Churchill, D. J., Daniels, L. D., … Waltz, A. E. M. (2021). Evidence for widespread changes in the structure, composition, and fire regimes of western North American forests. Ecological Applications, 31(8). 10.1002/eap.2431

- North, M., Stine, P., O’Hara, K., Zielinski, W., & Stephens, S. (2009). An ecosystem management strategy for Sierran mixed-conifer forests. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station. 10.2737/psw-gtr-220

- Swezy, C., Bailey, J., & Chung, W. (2021). Linking Federal Forest Restoration with Wood Utilization: Modeling Biomass Prices and Analyzing Forest Restoration Costs in the Northern Sierra Nevada. Energies, 14(9), 2696. 10.3390/en14092696

- Becker, D. R., McCaffrey, S. M., Abbas, D., Halvorsen, K. E., Jakes, P., & Moseley, C. (2011). Conventional wisdoms of woody biomass utilization on federal public lands. Journal of Forestry, 109(4), 208–218. 10.1093/jof/109.4.208

- Darlington, C., Moghaddas, Jason, & Fanslow, G. (2023). California forest biomass pile data collection. Joint Institute for Wood Products Innovation. https://cdnverify.bof.fire.ca.gov/media/fbplcgwm/california-forest-biomass-pile-data-collection_adamfk.pdf

- Barker, J., Voorhis, J., & Crotty, S. M. (2025). Assessing costs and constraints of forest residue disposal by pile burning. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 7. 10.3389/ffgc.2024.1496190

- Costa, T. (2025). Assessing the viability of wood recovery and utilization in Sonoma County. Regenerative Forest Solutions. https://www.regenerativeforestsolutions.org/resourcesandreports/full-study-assessing-the-viability-of-wood-recovery-and-utilization-in-sonoma-county

- Swezy, C., & Oldson, S. (2025). Assessing the feasibility of a joint powers authority-led sort yard in Northeastern California. Fall River Resource Conservation District. https://www.fallriverrcd.org/_files/ugd/80da86_a2c73d8b5788458f96777341f64cf965.pdf

- Delyser, K., Tase, N., Clay, K., Magnan, M., Evans, S., Keithley, C., Bartowitz, K., Gadoth-Goodman, D., Papa, C., Ontl, T., & Cooper, L. (2025). Effects of Forest Management & Wood Utilization on Carbon Sequestration & Storage in California. CAL FIRE. https://d3f9k0n15ckvhe.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/CBM_CA_report_FINAL.pdf

- Nabuurs, G.-J., Verkerk, P. J., Schelhaas, M.-J., González Olabarria, J. R., Trasobares, A., & Cienciala, E. (2018). Climate-Smart Forestry: mitigation impacts in three European regions (Vol. 6). EFI Helsinki, Finland.

- Tukman, M., & Griffith, E. (2022). North coast mechanical treatment feasibility: Assessing areas across the North Coast for mechanical treatment feasibility of hazardous fuels. North Coast Resource Partnership. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/d176adc01bcf465ab846a7d93e1d625c