JPA Funding Strategies 💵

For woody feedstock aggregation entities in California

Abstract¶

An analysis and strategy for securing sustainable funding for joint powers authorities (JPAs) as woody feedstock aggregators is introduced. JPA entities are proposed to improve forest product supply chain bottlenecks. Startup funding for each of the pilots is being funded by the California Governor’s Office for Land Use and Climate Innovation. Long-term, sustainable funding for each JPA will be challenging, especially in rural areas without the tax base to support wildfire mitigation authorities, such as Marin or JPAs, which help facilitate the utilization of wood from thinning projects. A portfolio approach to securing public and private funding, as well as self-sustaining revenue sources, is among several recommendations.

JPA Funding Strategies¶

Joint Powers Authorities (JPAs) are proposed as a solution for feedstock aggregation in California to broker agreements with forest landowners and managers and create long-term supply contracts to increase investor support for wood products businesses. Funding these entities presents challenges, given the difficulties of securing grants and private investments. Creating a diversified funding portfolio is crucial, especially for new entities, and suggestions for achieving this are provided.

Takeaways¶

- Portfolio strategy. Be strategic about what funds you utilize for different projects and programs. Look to foundations and business support grants for organizational startup or administrative costs. Still, there are implementation grants for field projects and private or bank loans for scaling once a feedstock aggregation entity is established.

- Temporal ramping. Revenue sources outside the realm of taxes and grants may be difficult to create and execute with risk-averse agencies and organizations. Try funding with traditional resources, such as grants, first, and then gradually introduce new resources to diversify your funding portfolio and help establish a new organization’s financial stability over time.

- Grant dependence & giving. In a similar vein, just because grants are available does not mean that will be the case indefinitely. As soon as you secure a grant or two, think about how to leverage them with other funding sources and work tirelessly to create more dependable and steady income sources than grants. It may seem daunting, but remember that the single largest source of charitable giving in the United States comes from individuals, not foundations, corporations, or grant-making agencies. The single largest source is also the least restricted type of funding, so it is critical for covering operational expenses (which are often underfunded by grants). Develop a strategy to cultivate local support through individual donations.

Background¶

The large wildfire seasons of the past five years were catastrophic for forests and communities. However, according to Keeley & Syphard (2021), these events are not unprecedented in recent California history and are typically associated with periods of drought, e.g., the 1920s and 2010s. According to North et al. (2022), tree densities in the Sierra Nevada over the past century increased by up to sevenfold, while average tree size decreased by 50%.

Not only does this overcrowding weaken forest health, but it is this excessively dense forest that causes fire to burn more severely. A meta-analysis led by Hagmann et al. (2021) showed a fire deficit and widespread alteration of ecological structure and function across seasonally dry forests of western North America. A chronic level of stress is created by high competition across tree stands, resulting in reduced resilience to drought, disease, fire, and climate change. North et al. (2009) advocates for an aggressive approach to treating fire-suppressed stands using an ecologically based approach that reduces the total number of trees/acre while maintaining stand heterogeneity.

Concerns¶

A significant cause for concern regarding the protection of old-growth forests in the United States is their decline from historical levels due to logging and development. DellaSala et al. (2022) highlight the fact that a large proportion of the remaining mature and old-growth forests on federal lands are still vulnerable to logging. The loss of these forests would not only diminish biodiversity but also release substantial amounts of stored carbon into the atmosphere.

Further compounding these concerns is the lack of a coordinated and effective national policy for old-growth conservation. Carroll et al. (2025) point to a history of policy debates, such as the National Old-Growth Amendment, which has failed to provide lasting protection. The authors advocate for a more comprehensive approach that extends beyond simple harvest restrictions to encompass landscape-level planning, the establishment of reserves, the protection of climate refugia, and the setting of specific goals for the recovery of species that depend on these unique habitats. Impacts on these forests also concern communities that rely on them for their water supplies.

However, let’s be very clear: thinning dense stands of fire-prone forests is entirely different from logging old-growth forests, and ecologically based thinning is not an excuse to log when maintaining stand heterogeneity and reducing fire risk are the primary treatment goals. Yet, misinformation about wildfire and forest treatments, similar to climate misinformation, persists (Jones et al. (2022)).

Managers implementing forest health treatments should adopt a tailored approach to increase forest resilience, mitigate fire risk, bring stands within a natural range of variation, and create forests that can thrive over the long term.[1] Treating mixed conifer stands on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada requires different treatments than mesic forests in the Pacific Northwest. Managers should take steps to reduce fire risk while still considering the negative impacts on biodiversity when planning any fire mitigation project.

Feedstock Aggregation¶

Thinned forests create a lot of biomass, and much of that biomass from forest health projects end up in burn piles or log decks and may stay in these locations indefinitely. Not only does this negate fire mitigation efforts, as burn piles and decks can promote or worsen fires, but the carbon from wood is also at risk of not being sequestered.

Processing biomass from thinning is challenging; Swezy et al. (2021) found that the cost of forest restoration far exceeds current market prices for biomass. Becker et al. (2011) point out that supply guarantees, industry presence, transportation, and the value of the biomass are limiting to utilization, whereas agency staffing, budgets, compliance, and partnership aggravated utilization problems rather than impeding progress. A burn pile inventory across California showed massive wood tonnages scattered through national forests and other lands Darlington et al., 2023. Yet burning those piles is likely more expensive than transporting them to a facility for processing (Barker et al 2024).

Transportation subsidies to move this feedstock to central locations or nearby facilities could be a crucial missing component in addressing the wildfire problem across the western United States.[2] Transporting the feedstock to a central location, accessible and central to processors, biomass facilities, and wood product businesses, would help move the biomass out of the woods, mitigating fire risk while also facilitating the centralization of long-term feedstock contracts with landowners and managing agencies.

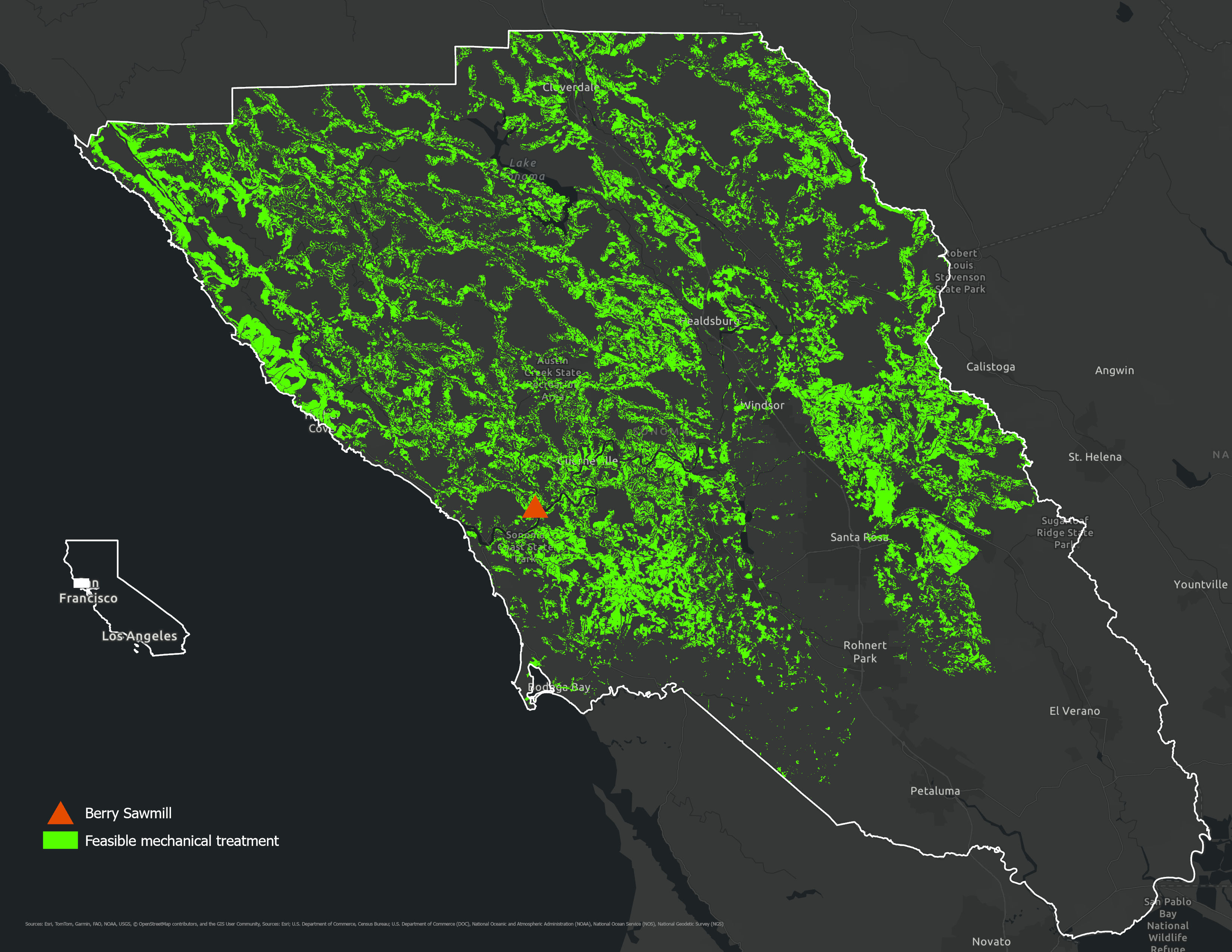

For instance, Regenerative Forest Solutions identified approximately half (242,365 acres) of Sonoma County’s forested acres as feasible for treatments (Figure 1). Berry Sawmill was identified as an ideal location for a wood products campus and aggregation yard Costa, 2025. Creating similar management entities across the West could make it easier for investors to conduct due diligence. Joint Powers Authorities may be an organizational template that can meet these needs.

Figure 1:Feasible treatment areas of Sonoma County and the location of Berry Sawmill as a feedstock aggregation site—adapted from Tukman & Griffith (2022). Feasible treatment areas exclude waterways, slopes above 45%, and material that is not within sufficient proximity to roadways.

Joint Powers Authority¶

Creating JPAs in some regions may be a solution to aggregate feedstock over large areas and provide it to process plants, mills, and other utilization entities. JPAs could act as brokers to facilitate long-term contracts between suppliers and processors, thereby driving investment in processing facilities. Most lenders and investors view wood product businesses as too risky without a minimum term contract of 10 years, preferably longer Darlington & Stevenson, 2023. For example, the USDA Forest Service, which manages 60% of California’s forests, typically allows a maximum of five years for a feedstock supply contract CSG, 2020.

What is a JPA?

Joint Powers Authorities are legally created entities that allow two or more public agencies to jointly exercise common powers Sousa Mills, 2016. A joint powers authority shares powers common to the member agencies, and those powers are outlined in the joint powers agreement. Joint powers are exercised when public officials from more than two agencies agree to create a new legal entity or establish a joint approach to address a common problem, fund a project, or serve as a representative body for a specific activity. Examples of areas where JPAs are used commonly include groundwater management, road construction, and habitat conservation Cypher & Grinnell, 2007.

An example of a JPA being developed for feedstock aggregation is located in the northeastern corner of the state. The development of this specific JPA is a key component of the California Forest Residual Aggregation for Market Enhancement (CALFRAME) pilot, funded by the Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation. The finance strategy for a JPA is adapted from this broader effort, with more detail available from Darlington & Stevenson (2023).

In establishing the JPA, partners have been clear about its role: to act as a critical entity for wood utilization without competing for funds with other organizations, such as Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs), sawmills, or licensed timber operators (LTOs). This approach requires a realistic revenue assessment and a plan for the initial five years of operation, acknowledging that creating a stably funded JPA will be challenging given the wide fluctuations in private and public funding. But how can such an entity be funded in rural counties with low tax bases that cannot support a sales tax to develop sustainable revenue for a new entity?[3]

LTO and RCD role in forest management

Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs) are quasi-governmental, non-regulatory agencies based in California’s counties, providing critical resources, funding, and training to address forest health. There are approximately 40 RCDs with forestry programs that focus on implementing thinning, prescribed fire, and providing technical assistance to private landowners, as well as collaborating with other organizations (CARCD).

Licensed Timber Operators (LTOs) are the loggers licensed to operate forestry operations in the state of California. They are licensed under the state’s Forest Practice Act Law and authorized to conduct tree cutting and removal (CAL FIRE). During the past decade, LTOs have been critical to carrying out forest health projects funded by CAL FIRE and others to reduce wildfire risk and improve forest resilience. Their limited numbers have at times curtailed forest health projects.

Funding Options¶

The abundance of state and federal funding over the past five years has meant that many agencies and organizations depend on grant funding for implementing restoration and infrastructure projects. Trump administration cuts in 2025 demonstrate the vulnerability of relying too heavily on grant funding. Many nonprofits are familiar with the cyclic nature of many funding sources.

Traditional¶

The Northeast California feedstock aggregation project recognized the need for grant funding to initiate a JPA and acknowledged the need for additional funding sources that can sustainably support a JPA over time. These are described below, and with the pluses and minuses of each summarized in (Table 1).

- Endowment. In the case of the feedstock aggregation pilots, the Office of Land Use and Climate Change Innovation provided a funding tranche for entity startups. This funding could be used to create an endowment or, at the very least, seed an endowment that could provide a steady source of unrestricted revenue if invested wisely. Other JPAs could do the same with an initial foundation grant or a campaign to raise sufficient funds to start an endowment.

- Contributions. Regardless of starting an endowment, a capital campaign to raise awareness about a JPA and generate individual, corporate, and foundation grants would complement any secured public funds. A match from non-public sources often makes grant applications more competitive. A strong JPA strategy that outlines the mission, programs, and projects is critical for focusing funding requests. Similarly, for any grant application, it prioritizes which funding to pursue (Forest Business Alliance).

- Federal and State Grants. It is unlikely that a JPA will receive operational funding from state and federal grants, but any proposals it leads or participates in could charge overhead (~10%) plus directly bill salaries to cover some operating costs. A negotiated indirect cost rate agreement, or NICRA, to increase this value through public grants could be another long-term strategy to boost operating cost revenues.

- Member Contributions. In the case of the Northeast California pilot, members, such as RCDs, pay an annual cost to participate in the program.

- Fee for Service. Western Shasta RCD, for example, works with non-industrial forest owners and offers services to support forest management plans for small forested landowners. The State can fund the development of forest management plans for private landowners. A JPA could offer similar services as long as it does not compete with RCDs in the region.

- Sort yards. Managing a sort yard for aggregated feedstock would be a strategic revenue source. This would require a substantial investment in equipment and a suitable site. A feasibility study would help understand the total costs, potential revenue, and risk reduction associated with the yard.

Table 1:Analysis of funding types appropriate to aggregation JPAs. Timing roughly refers to the amount of time required to generate income. Difficulty is a qualitative scale ranging from 1 (easiest to secure) to 5 (most difficult).

| Type | Pluses | Minuses | Timing | Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endowment | Steady income from principal | Need significant amounts to generate income | May take a long time to build principal | 5 |

| Individual Contributions | Unrestricted funding | Much time to manage individual contributions | Instant | 1 |

| Public Grants | Access to large amounts of money | Reimbursable, administration costs can be high, stiff competition, cyclic | Public grants may take up to 1 year to contracting from proposal submittal | 3 |

| Private Grants | Often include unrestricted funding | Dependent on relationships with program officers, board members | Lengthy time for relationship building | 2 |

| Fee-for-Service | Steady income based on capacity and experience for services | Staffing, uneveness of demand | Long time to develop and market services | 3 |

| Sort Yard | Steady income, demand for wood high | Transportation costs, management, long-term supply | Permitting and capacity building may take a long time | 4 |

Temporal Adoption¶

In general, the feasible options identified are traditional and similar to funding approaches for an RCD or nonprofit.

- New finance options, such as environmental impact bonds, could be introduced over a longer period and trialed at a small scale, then scale up when successful. These could also include other financial mechanisms, such as revolving loan funds (offering low-interest loans), public-private partnerships, or bonds.

- Other revenue-generating options could be tested in the same manner to ensure their effectiveness and introduce them to skeptical participants, financial managers, or government entities that are not used to working with alternative finance options.

Collaborative Finance¶

Collaborative finance is a conservation finance strategy that involves cooperative interaction between individual project developers, stakeholders, and finance providers (Russell and Odefey 2024). This process may or may not include traditional financial institutions.[4] The term can be broadened to include finance developed through the fair and equitable participation of stakeholders in a region, landscape, or watershed, addressing natural resource and infrastructure management needs, and utilizing multiple forms of funding, from public grants to private investment. Finance approaches may include outcomes-based finance models such as environmental impact bonds.

New Funding Options

New Finance Options Conservation finance options include environmental impact bonds, such as Blue Forest’s Forest Resilience Bond, which leverages private investment from impact investors to support forest health projects. Repayment to investors is supported over time by beneficiaries based on the savings and benefits from reduced wildfire risks and improved ecosystem services. A JPA could utilize environmental impact bonds on a trial basis at a small scale and then expand over an extended period. Identifying potential payor entities interested in covering the avoided costs of wildfire through proactive measures, such as thinning and prescribed fire, is worth pursuing immediately or as soon as an executive director is hired.

We do not recommend relying solely on impact bonds, as they take a lengthy time to develop and rely on a payor to provide avoided cost funding. However, a bond could be a valuable complementary funding resource to other secured revenues. Other ‘newer’ finance options could include the following:

Carbon Markets Carbon markets offer an opportunity to secure funding for on-the-ground forest management activities, including thinning, pruning, mastication, mechanical treatment, and prescribed burning. Revenue realized through the carbon market could help a JPA to treat more forest land than otherwise possible and generate additional biomass that could be put under supply contracts to support existing and emerging infrastructure. Market prices for carbon credits vary depending on a given project’s size, location, treatment type, and the specific carbon market or registry used. Carbon credits can be generated for projects of any size, regardless of their location on federal, state, or private lands. Refer to the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol section for an alternative approach that is easier to implement than carbon sequestration credits or markets, as the avoided costs are already calculated, and proponents do not need to seek an entity to purchase the credits.

The National Forest Foundation implemented several voluntary carbon projects in California and the West following wildfires. Funded by corporate donors, the projects created carbon based on the growth trajectories of planted trees. The credits were registered with the American Carbon Registry but were immediately retired upon creation, as trading carbon on public lands is prohibited.

Avoided Wildfire Emissions The Spatial Informatics Group and Element Markets developed a forecast methodology under the Climate Forward program to recognize the climate benefits associated with fuel treatment activities that reduce the risk of catastrophic forest fires and their associated emissions. Known as the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Forecast Methodology, the Climate Action Reserve protocol could provide complementary funding for thinning and prescribed fire projects, in addition to grants and private investments. The Protocol differs from carbon offsets in that forecasted mitigation units (FMUs) are issued for forecasted reductions or removals of greenhouse gases. FMUs are used to mitigate anticipated future emissions, such as wildfires.

Embodied Carbon Although it may be several years from implementation, developing and marketing low-carbon building materials is another new opportunity. Buildings are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, making building decarbonization a California state priority. Embodied carbon is the lifecycle of greenhouse gas emissions from creating, transporting, and disposing of building materials (Carbon Leadership Forum, 2022). In other words, embodied carbon is any building’s carbon footprint contained in its building materials. It differs from operational carbon, the carbon produced by a building’s energy, heat, and lighting. The California Air Resources Board is developing a comprehensive strategy for embodied carbon and is seeking comments following the signing of ABs 2446 and 43.

Revolving Loan Funds Pooled funding sources, such as impact bonds or revolving loan funds, can help make a greater amount of funds available to more projects across a landscape. Typically offered at lower-than-market interest rates, revolving loan funds are self-replenishing pools of money that utilize principal and interest payments on existing loans to issue new loans. They have been used effectively on small to large scale to develop businesses, assist healthcare, and improve environmental outcomes. Revolving loan funds also provide much-needed upfront capital for project startups. They are flexible and can be used in conjunction with more conventional funds, such as grants and loans.

For example, through a coalition of public and private partners, the Southwest Wildfire Impact Fund aims to utilize resources from private investors and revenues generated from biomass produced through forest thinning to offset the financial burden of wildfire mitigation in the San Juan National Forest’s wildland-urban interface. The project fosters regional collaboration through shared project financing and implementation. It also creates the opportunity for scaling up forest treatments and fire reduction by creating a revolving loan fund that reinvests proceeds into additional projects, ensuring that capital is available for long-term re-treatment and expansion of forest health interventions.

Blue Forest is operating a revolving loan fund called the California Wildfire Innovation Fund, which could expand into broader support for other forest health entities.

Parametric Insurance Parametric or index-based insurance covers the probability of a predefined event, rather than indemnifying the actual loss incurred Re, 2023. These so-called trigger events are typically disaster-related (e.g., wildfires, flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes). They are measured through triggers such as wind speed, earthquake magnitude, acres burned, burn severity, or rainfall amount. Insurable triggers are modeled and must happen by chance. When the triggers are reached, a predetermined payout is made regardless of the sustained physical losses. Parametric insurance is meant to complement existing indemnity insurance but is increasingly used for post-disaster restoration funding in the natural world.

One of the earliest examples of parametric insurance used for nature recovery is the Mesoamerican Reef parametric insurance that provided $800,000 for reef restoration following Hurricane Delta. The trigger was windspeed with a parameter greater than 100 knots. The funds originated from the Coastal Zone Management Trust. Utilizing insurance to protect forests and communities, likely through wildfire risk mitigation, could be a novel approach to funding activities throughout the region and provide complementary funds that could be particularly valuable post-fire.

Tech-based Solutions The technology could help connect funders to a new JPA. Blockchain and digital solutions have mostly been applied to reforestation and carbon sequestration projects. It may be possible to establish a digital marketplace where funders and implementers can connect and collaborate on implementing forest health restoration and infrastructure projects. Developing a platform for aggregated funding could be part of a funded project or developed in tandem rather than as a standalone initiative.

Budget¶

CAL FRAME partners estimated an approximate annual budget averaging $400,000 during the 1st three years of operation and based on similar operating expenses for RCDs in the region (Table 2).

Table 2:Three-year hypothetical JPA budget showing revenue and expenses.

| ITEM | YR1 | YR2 | YR3 | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REVENUE | ||||

| Contributions | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 | 180,000 |

| Grants | 60,000 | 120,000 | 150,000 | 330,000 |

| Fee-for-Service | 140,000 | 220,000 | 330,000 | 690,000 |

| TOTAL REVENUE | 260,000 | 400,000 | 540,000 | 1,200,000 |

| EXPENSES | ||||

| Labor | 340,000 | 370,000 | 410,000 | 1,120,000 |

| Operations | 20,000 | 30,000 | 40,000 | 90,000 |

| Outreach | 2,000 | 3,000 | 4,000 | 9,000 |

| TOTAL EXPENSES | 362,000 | 403,000 | 454,000 | 1,219,000 |

Revenue¶

Revenue contributions include contributions, grants, and fee-for-service consulting. Contributions and gifts may come from local to regional foundations and corporations interested in forest health. Individual contributions always have the potential to add up to more than foundation and corporate gifts, but they require more time to manage. Creating a time-bound campaign with a specific fundraising goal replete with a thermometer to show progress could be a great way to involve communities in the region through giving and creating outreach or communications opportunities at the same time to explain the need for a JPA and the importance of sustainable funding from the community to protect homes, infrastructure, and forests.

In the case of pilot projects supported by the Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation, a tranche of endowment-like funding is being provided for startup funding of aggregation entities. In some cases, this amount is as much as $1 million, which, along with a capital campaign to bolster individual giving and create awareness around a JPA, could create a base endowment and provide stable operational revenue to a new organization from the principal if the endowment funds are wisely invested.

Although not competing for grants with RCDs, a JPA may help administer a large grant across multiple RCDs to leverage more funds across a region. With the devolution of some state funding sources, this could be a great option for managing those funds and reducing competition for funding resources, as the grants are allocated to local organizations. The fee-for-service section includes an item for grant administration. It also includes an option for implementing landowner forest plans, as this may be a viable revenue source and could help source wood. A sort yard managed by the JPA to source, centralize, and sell woody biomass is another revenue option, but will require investment to be successful. Expenses for the sort yard are included in the expenses section.

JPA - RCD competition

Evaluating whether to form a new governmental entity or organization is an important consideration for feedstock aggregation. Working with existing organizations, such as Resource Conservation Districts or Fire Safe Councils, would be a good starting point. It is critical to incorporate into the JPA’s bylaws and revenue-generating practices that grant fundraising does not compete with RCDs. It is possible a JPA may collaborate on a grant with one or more RCDs but should never submit grants for which an RCD qualifies.

Contingency funding should be written into the budget expenses. Adding 10-15% contingency line items to any secured grant would supplement that funding; however, most grant funding contingencies are typically applied to budget shortfalls. Other contingency funding sources could include unrestricted funding (such as contributions or gifts) and a higher indirect rate.

Expenses¶

An annual expense budget of ~$ $400,000 is estimated for a JPA startup. The total expenses/year slowly ramp up each year of the budget with the idea that with additional secured revenue, a JPA would bring on more staff capacity and increase offerings, reach, or fee-for-service activities such as additional sort yards. The bulk of the expenses is for labor and staff, including an executive director, a contracted feedstock manager, an administrative bookkeeper, and various contracted services. Briefly, the staff responsibilities are the following:

- Executive Director. Manage board of directors, lead program development/outreach/education/fundraising/communications, develop an annual budget, manage contracts, recruit and manage staff.

- Administrative Bookkeeper. Track/invoice budget, develop cost allocation plan, manage grant reporting, administer payroll, manage AP/AR accounts, prepare 1099s and tax docs, develop grant budgets, and ensure financial compliance.

- Feedstock Manager. Source and sell feedstock from public and private lands, arrange transport to sort yard(s), manage sort yards, develop outreach materials, manage compliance documents for sort yard and aggregation, and maintain records.

Other expenses include operations and maintenance, audit and legal fees, insurance, equipment, software, travel, and bank fees. Expenses include communications, website development, outreach, equipment, insurance, and land lease costs for a sort yard.

Timeline¶

An approximate timeline for key activities to fund and operationalize a JPA is shown in Table 3. Endowment seed funding and a capital campaign will be critical to initiate the endowment. Staffing is described under expenses and shows the approximate start time for each staff member. The development of JPA bylaws will define governance, and JPA will be created when the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO) filing is completed.

Table 3:Timeline for a theoretical JPA startup period.

| Task | Sub-task | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Revenue Generation | Endowment creation | X | X | X | |||

| Gift campaign | X | X | X | ||||

| Fee-service | X | X | X | X | |||

| Sort yard 1 | X | ||||||

| Sort yard 2 | X | ||||||

| 2. Staffing | Executive director | X | |||||

| Administrator | X | ||||||

| Feedstock manager | X | ||||||

| 3. Governance | JPA bylaws | X | X | ||||

| LAFCO filing | X |

Recommendations¶

Funding JPAs is not a simple task, as most public funding sources are focused on project implementation, e.g., funding restoration projects in the field, rather than providing administrative support or organizational startup. Some foundations fund this type of work, but accessing those funds can be challenging. Another challenge is competing with existing entities for scarce local, regional, and federal resources. The following are recommendations to consider when examining the feasibility of building and maintaining a JPA for feedstock aggregation:

- Utilize public funds for startup and traditional projects. Public funding is readily available and generally suitable for trials or the initial development of feasible but new ideas.

- Pilot non-traditional, higher risk, or new revenue sources as pilots. Then, ramp them up with success, and participating entities and partners see their value and understand how they work.

- Co-house staff and resources. Utilize existing offices and share staff and other resources as capacity and funding allow. This is particularly important during the startup and early phases of developing a JPA.

- Incorporate feedstock insurance. To de-risk feedstock pricing and attract new investors to wood product businesses.

- Leverage public funds with private investment. When public funds are secured, immediately work to leverage them with other public and private funding resources. Don’t wait until near the end of the grant cycle to look for additional funds.

- Sort yards with wood campuses or easements. Could land trusts or agencies that fund easements include sort yards as part of restoration efforts?

- Use the right revenue source. Property and sales tax increases are more effective in populated areas with higher incomes; however, they are usually not appropriate for disadvantaged rural areas, where the tax base and population tend to be too low to provide sufficient funding.

Acknowledgments¶

A special thank you to Joshua Harrison, Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, and Temra Costa, Forestree Collective, for reviewing the draft manuscript.

See Bohlman et al., 2021.

The old rule of thumb is a maximum 50-mile deadhead (empty trailer returning after dropping off payload) trip for timber or other forest products.

JPAs similar to the Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority, funded through sales tax increase, aren’t possible in northeastern California, where a low tax base and few people cannot generate the same income as a more densely populated county such as Marin.

See collaborative finance for more information.

- Keeley, J. E., & Syphard, A. D. (2021). Large California wildfires: 2020 fires in historical context. Fire Ecology, 17(1). 10.1186/s42408-021-00110-7

- North, M. P., Tompkins, R. E., Bernal, A. A., Collins, B. M., Stephens, S. L., & York, R. A. (2022). Operational resilience in western US frequent-fire forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 507, 120004. 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.120004

- Hagmann, R. K., Hessburg, P. F., Prichard, S. J., Povak, N. A., Brown, P. M., Fulé, P. Z., Keane, R. E., Knapp, E. E., Lydersen, J. M., Metlen, K. L., Reilly, M. J., Sánchez Meador, A. J., Stephens, S. L., Stevens, J. T., Taylor, A. H., Yocom, L. L., Battaglia, M. A., Churchill, D. J., Daniels, L. D., … Waltz, A. E. M. (2021). Evidence for widespread changes in the structure, composition, and fire regimes of western North American forests. Ecological Applications, 31(8). 10.1002/eap.2431

- North, M., Stine, P., O’Hara, K., Zielinski, W., & Stephens, S. (2009). An ecosystem management strategy for Sierran mixed-conifer forests. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station. 10.2737/psw-gtr-220

- DellaSala, D. A., Mackey, B., Norman, P., Campbell, C., Comer, P. J., Kormos, C. F., Keith, H., & Rogers, B. (2022). Mature and old-growth forests contribute to large-scale conservation targets in the conterminous United States. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 5. 10.3389/ffgc.2022.979528

- Carroll, C., Noon, B. R., Masino, S. A., & Noss, R. F. (2025). Coordinating old-growth conservation across scales of space, time, and biodiversity: lessons from the US policy debate. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 8. 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1493879

- Jones, G. M., Vraga, E. K., Hessburg, P. F., Hurteau, M. D., Allen, C. D., Keane, R. E., Spies, T. A., North, M. P., Collins, B. M., Finney, M. A., Lydersen, J. M., & Westerling, A. L. (2022). Counteracting wildfire misinformation. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 20(7), 392–393. 10.1002/fee.2553

- Swezy, C., Bailey, J., & Chung, W. (2021). Linking Federal Forest Restoration with Wood Utilization: Modeling Biomass Prices and Analyzing Forest Restoration Costs in the Northern Sierra Nevada. Energies, 14(9), 2696. 10.3390/en14092696

- Becker, D. R., McCaffrey, S. M., Abbas, D., Halvorsen, K. E., Jakes, P., & Moseley, C. (2011). Conventional wisdoms of woody biomass utilization on federal public lands. Journal of Forestry, 109(4), 208–218. 10.1093/jof/109.4.208

- Darlington, C., Moghaddas, Jason, & Fanslow, G. (2023). California forest biomass pile data collection. Joint Institute for Wood Products Innovation. https://bof.fire.ca.gov/media/0t1f0oqa/full-12-b-i-ca-forest-biomass-pile-data-collection-report-draft_part-1__11-8-23-adamfk.pdf

- Barker, J., Voorhis, J., & Crotty, S. M. (2025). Assessing costs and constraints of forest residue disposal by pile burning. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 7. 10.3389/ffgc.2024.1496190

- Costa, T. (2025). Assessing the viability of wood recovery and utilization in Sonoma County. Regenerative Forest Solutions. https://www.regenerativeforestsolutions.org/resourcesandreports/full-study-assessing-the-viability-of-wood-recovery-and-utilization-in-sonoma-county

- Tukman, M., & Griffith, E. (2022). North coast mechanical treatment feasibility: Assessing areas across the North Coast for mechanical treatment feasibility of hazardous fuels. North Coast Resource Partnership. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/d176adc01bcf465ab846a7d93e1d625c

- Darlington, C., & Stevenson, C. (2023). Joint Powers Authorities: A tool to manage forest biomass residuals in California. CLERE, Inc. https://bof.fire.ca.gov/media/sbvcxfiy/cal-frame-jpa-noreast-opr-pilot_final-may122023.pdf

- CSG. (2020). Forest resilience authorities (FRAs): How regional wood waste management can support forest health and economic development goals in California. Conservation Strategy Group. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wPsETRE7AewydAGzFuuZoFvQkKNaFh6r/view